|

Introduction

The value and importance of the army were realized very early in the

history of India, and this led in course of time to the maintenance

of a permanent militia to put down dissensions. War or no war, the

army was to be maintained, to meet any unexpected contingency. This

gave rise to the Ksatriya or warrior caste, and the ksatram dharman

came to mean the primary duty of war. To serve the country by

participating in war became the svadharma or this warrior community.

The necessary education, drill, and discipline to cultivate

militarism were confined to the members of one community, the

Ksatriyas. This prevented the militant attitude from spreading to

other communities and kept the whole social structure unaffected by

actual wars and war institutions.

Says the Arthva Veda:

"May we revel, living a hundred

winters, rich in heroes."

The whole country looked upon the

members of the ksatriya community as defenders of their country and

consequently did not grudge the high influence and

power wielded by

the Ksatriyas, who were assigned a social rank next in importance to

the intellectual and spiritual needs of the society. power wielded by

the Ksatriyas, who were assigned a social rank next in importance to

the intellectual and spiritual needs of the society.

The ancient

Hindus were a sensitive people, and their heroes were instructed

that they were defending the noble cause of God, Crown and

Country.

Viewed in this light, war departments were 'defense' departments and

military expenditure were included in the cost of defense. In this,

as in many cases, ancient India was ahead of modern ideas.

Chivalry, individual heroism, qualities of mercy and nobility of

outlook even in the grimmest of struggles were not unknown to the

soldiers of ancient India. Thus among the laws of war, we find that,

(1) a warrior (Khsatriya) in

armor must not fight with one not so clad

(2) one should fight only one

enemy and cease fighting if the opponent is disabled

(3) aged men, women and

children, the retreating, or one who held a straw in his

lips as a sign of unconditional surrender should not be

killed

It is of topical interest to note that

one of the laws enjoins the army to leave the fruit and flower

gardens, temples and other places of public worship unmolested.

Terence Duke, author of

The Boddhisattva

Warriors: The Origin, Inner Philosophy, History and Symbolism of the

Buddhist Martial Art Within India and China, martial arts went from India to China. Fighting

without weapons was a specialty of the ancient Ksatreya warriors of

India.

Back to Contents

Territorial

ideal of a one-State India

Imperial sway in ancient India meant the active rule of an

individual monarch who by his ability and prowess brought to

subjection the neighboring chieftains and other rulers, and

proclaimed himself the sole ruler of the earth. This goes by the

name of digvi-jaya. It is not necessary that he should conquer all

States by the sword. A small state might feel the weight of a

conquering king and render obeisance of its own accord.

According to the Sangam classics, each of the respective rulers of

the chief Tamil kingdoms, the Cera, Cola and Pandya, carried his

sword as far north as the Himalayas, and implanted on its lofty

heights his respective crest the bow, the tiger and the fish. In

these adventures which the Tamil Kings underwent for their

glorification, they did not lag behind their northern brethren. The

very epithet Imayavaramban shows that the limits of the empire under

that Emperor extended to the Himalayas in the north.

This title was

also earned by Ceran Senguttuvan by his meritorious exploits in the

north. Names like the Cola Pass in the Himalayan slopes, which in

very early times connected Nepal and Bhutan with ancient Tibet, give

a certain clue to the fact that once Tamil kings went so far north

as the Himalayas and left their indelible marks in those regions.

Kshatriya Warrior (Now in Indian Museum, Calcutta).

If in the epic age a Rama and an

Arjuna could come to the extremity

of our peninsula, and in the historical period of a Chandragupta or

a Samudragupta could undertake an expedition to this part of our

country, nothing could prevent a king of prowess and vast resources

like the Cera king Senguttuvan from carrying his

armies to the

north. The route lay through the Dakhan plateau, the Kalinga, Malva,

and the Ganga. Perhaps it was the ancient Daksinapatha route known

to history from the epoch of the Rg Veda Samhita. armies to the

north. The route lay through the Dakhan plateau, the Kalinga, Malva,

and the Ganga. Perhaps it was the ancient Daksinapatha route known

to history from the epoch of the Rg Veda Samhita.

The king who became conqueror of all India was entitled to the

distinction of being called a Samrat. In the Puranic period the

great Kartavirya Arjuna of the Haihaya clan spread his arms

throughout the ancient Indian continent and earned the title of

Samrat.

The same principle of glory and distinction underlay the

performance of the sacrifice, Asvamedha and Rajasuya, which were

intended only for the members of the Ksatriya community.

This bears testimony to ' the existence of the territorial ideal of

a one-State India' (Cakravartiksetram of Kautalya). These kings were

called Sarvabhaumas and Ekarats.

Vedic kings aimed at it, and epic rulers realized it. The idea of

ekarat, continued down to Buddhist times and even later. The Jatakas

which are said to belong to the fifth and sixth century B.C., make

pointed reference to an all-Indian empire.

This concept of an

all-India empire stretching from Kanyakumari to the Himalayas,

according to Kautalya receives further support from another

important political term: ekacchatra, or one-umbrella sovereignty.

Hindus have given shelter to the persecuted people from many lands

and in all ages. But what is most important, they have always

regarded their own homeland as the only playfield for their

chakravartins, and never waged wars of conquest beyond the borders

of Bharata-varsha.

Back to Contents

The Laws of

War

When society became organized and a warrior caste (Kshatriya) came

into being, it was felt that the members of this caste should be

governed by certain humane laws, the observance of which, it was

believed, would take them to heaven, while their non-observance

would lead them into hell. In the post Vedic epoch, and especially

before the epics were reduced to writing, lawless war had been

supplanted, and a code had begun to govern the waging of wars. The

ancient law-givers, the reputed authors of the Dharmasutras and the

Dharmasastras, codified the then existing customs and usages for the

betterment of mankind. Thus the law books and the epics contain

special sections on royal duties and the duties of common warriors.

It is a general rule that kings were chosen from among the Kshatriya

caste. In other words, a non-Ksatriya was not qualified to be a

king. And this is probably due to the fact that the kshatriya caste

was considered superior to others in virtue of its material prowess.

Though the warrior's code enjoins that all the Ksatriyas should die

on the field of battle, still in practice many died a peaceful

death. There is a definite ordinance of the ancient law books

prohibiting the warrior caste from taking to asceticism.

Action and

renunciation is the watch-word of the Ksatriya. The warrior was not

generally allowed to don the robes of an ascetic. But Mahavira and

Gautama protested against these injunctions and inaugurated an order

of monks or sannyasins. When these dissenting sects gathered in

strength and numbers, the decline of Ksatriya valor set in. Once

they were initiated into a life of peace and prayer, they preferred

it to the horrors of war. this was a disservice that dissenting

sects did to the cause of ancient India.

When a conqueror felt that he was in a position to invade the

foreigner's country, he sent an ambassador with the message: 'Fight

or submit.'

More than 5000 years ago India recognized that the

person of the ambassador was inviolable. This was a great service

that ancient Hinduism rendered to the cause of international law. It

was the religious force that invested the person of the herald or

ambassador with an inviolable sanctity in the ancient world.

The

Mahabharata rules that the king who killed an envoy would sink into

hell with all his ministers.

The Mahabharata War

Dharmayuddha is war carried on the principles of Dharma, meaning

here the Ksatradharma or the law of Kings and Warriors.

The Hindu laws of war are very chivalrous and humane, and prohibit

the slaying of the unarmed, of women, of the old, and of the

conquered.

Megasthenes noticed a peculiar trait of Indian warfare they never

ravage an enemy's land with fire, nor cut down its trees.

The Bhagavad Gita has influenced great Americans from Thoreau to

Oppenheimer.

Its message of letting go of the fruits of one’s

actions is just as relevant today as it was when it was first

written more than two millennia ago.

As early as as the 4th century B.C. Megasthenes noticed a peculiar

trait of Indian warfare.

"Whereas among other nations it is usual, in the contests of war, to

ravage the soil and thus to reduce it to an uncultivated waste,

among the Indians, on the contrary, by whom husbandmen are regarded

as a class that is sacred and inviolable, the tillers of the soil,

even when battle is raging in their neighborhood, are undisturbed by

any sense of danger, for the combatants on either side in waging the

conflict make carnage of each other, but allow those engaged in

husbandry to remain quite unmolested. Besides, they never ravage an

enemy's land with fire, nor cut down its trees."

(source: A Brief History of India - By Alain Danielou p. 106).

The

modern "scorched earth" policy was then unknown. "

Professor H. H. Wilson says:

"The Hindu laws of war are very

chivalrous and humane, and prohibit the slaying of the unarmed, of

women, of the old, and of the conquered."

At the very time when a battle was going on, be says, the

neighboring cultivators might be seen quietly pursuing their work, -

" perhaps ploughing, gathering for crops, pruning the trees, or

reaping the harvest." Chinese pilgrim to Nalanda University, Hiuen

Tsiang affirms that although the there were enough of rivalries and

wars in the 7th century A.D. the country at large was little injured

by them.

Back to Contents

Weapons of War

as Gathered from Literature

Dhanur Veda classifies the weapons of offence and defense into four

- the mukta, the amukta, the mukta-mukta and the yantramukta. The

Nitiprakasika, on the other hand, divides them into three broad

classes, the mukta (thrown), the amukta (not thrown), and the

mantramukta (discharged by mantras).

The bows and arrows are the

chief weapons of the mukta group.

The very fact that our military

science named Dhanur Veda provides sufficiently clearly that the bow

and arrow were the principle weapons of war in those times. It was

known by different terms as sarnga, kodanda, and karmuka. Whether

these are synonyms of the same thing or were different is difficult

to say. The Rg vedaic smith was not only a steel worker but also an

arrow maker.

Fire-Arms:

It would be interesting to examine the true nature of the

agneya-astras. Kautalya describes agni-bana, and mentions three

recipes - agni-dharana, ksepyo-agni-yoga, and visvasaghati.

Visvasaghati was composed of 'the powder of all the metals as red as

fire or the mixture of the powder of kumbhi, lead, zinc, mixed with

the charcoal and with oil wax and turpentine.' From the nature of

the ingredients of the different compositions it would appear that

they were highly inflammable and could not be easily extinguished.

A recent writer remarks:

'The Visvasaghati-agni-yoga was virtually a

bomb which burst and the fragments of metals were scattered in all

directions. The agni-bana was the fore-runner of a gun-shot.....

Sir A. M. Eliot tells us that the Arabs learnt the manufacture of

gunpowder from India, and that before their Indian connection they

had used arrows of naptha. It is also argued that though Persia

possessed saltpetre in abundance, the original home of gunpowder was

India. It is said that the Turkish word top and the Persian tupang

or tufang are derived from the Sanskrit word dhupa. The dhupa of the

Agni Purana means a rocket, perhaps a corruption of the Kautaliyan

term natadipika.

(source: Fire-Arms in Ancient India - By Jogesh Chandra Ray I.H.Q.

viii. p. 586-88).

Heinrich Brunnhofer (1841-1917), German Indologist, also believed

that the ancient Aryans of India knew about gunpowder.

(source: German Indologists: Biographies of Scholars in Indian

Studies writing in German - By Valentine Stache-Rosen. p.92).

Gustav Oppert (1836-1908) born in Hamburg, Germany, he taught

Sanskrit and comparative linguistics at the Presidency College,

Madras for 21 years. He was the Telugu translator to the Government

and Curator, Government Oriental Manuscript Library. Translated

Sukraniti, statecraft by an unknown author. Gustav Oppert (1836-1908) born in Hamburg, Germany, he taught

Sanskrit and comparative linguistics at the Presidency College,

Madras for 21 years. He was the Telugu translator to the Government

and Curator, Government Oriental Manuscript Library. Translated

Sukraniti, statecraft by an unknown author.

He attempted to prove that ancient Indians knew firearms.

(source:

German Indologists: Biographies of Scholars in Indian

Studies writing in German - By Valentine Stache-Rosen. p.81. For more refer to article by G R Josyer -

India: The Home of

Gunpowder and Firearms).

In his work, Political Maxims of the Ancient Hindus, he says, that

ancient India was the original home of gunpowder and fire-arms. It

is probable that the word Sataghni referred to in the Sundara Kanda

of the Ramayana refers to cannon.

(source: Hindu Culture and The Modern Age - By Dewan Bahadur K.S.

Ramaswami Shastri - Annamalai University 1956 p. 127).

The word astra in the Sukraniti is interpreted by Dr. Gustav Oppert

as a bow. The term astra means a missile, anything which is

discharged. Agneya astra means a fiery arm as distinguished from a

firearm.

Dr. Oppert refers to half a dozen temples in South India to prove

the use of fire-arms in ancient India. The Palni temple in the

Madura District contains on the outer portion in an ancient stone

mantapa scenes of carved figures of soldiers carrying in their hands

small fire-arms, apparently the small-sized guns mentioned in the

Sukranitisara.

Again in the Sarnagapani temple at Kumbakonam in the

front gate of the fifth story from the top is the figure of a king

sitting in a chariot drawn by horses and surrounded by a number of

soldiers. Before this chariot march two sepoys with pistols in their

hands. In the Nurrukkal mantapam of the Conjeevaram temple is a

pillar on the north side of the mandapa. Here is a relief vividly

representing a flight between two bodies of soldiers. Mounted

horsemen are also seen.

The foot-soldier is shown aiming his

fire-arm against the enemy. Such things are also noted in the Tanjore temple and the temple at Perur, in the Coimbatore District.

In the latter there is an actual representation of a soldier loading

a musket.

The Borobudar in Java where Indian tradition is copied wholesale.

They are ascribed roughly to the period 750-850 A.D. There is a

striking relief series PL. I, fig. 5, (1605) representing a battle

in which two others are seen on each side, one wearing a curved

sword in the right hand and a long shield, and the other a mace and

a round shield resembling a wheel, all apparently made of iron. The

story of the Ramayana is also given as in the Tadpatri temple from

Rama's going to the forest down to the killing of Ravana. There is

also a wonderful sculpture of an ancient Hindu ship.

(source: Suvarnadvipa - By R.C. Majumdar. pp 194-5).

Medhatithi remarks thus "while fighting his enemies in battle, he

shall not strike with concealed weapons nor with arrows that are

poisoned or barbed on with flaming shafts."

Sukraniti while referring to fire-arms, (agneyastras) says that

before any war, the duty of the minister of war is to check up the

total stock of gunpowder in the arsenal. Small guns is referred as

tupak by Canda Baradayi. The installation of

yantras (engines of

war) inside the walls of the forts referred to by Manasollasa and

the reference of Sataghni (killer of hundreds of men) pressed into

service for the protection of the forts by Samaranganasutradhara

clearly reveals the frequent use of fire arms in the battle-field.

(source:

India Through The Ages: History, Art Culture and Religion -

By G. Kuppuram p. 512-513).

Lord Rama with his bow defeats Ravana in the gold city of Lanka.

In the light of the above remarks we can trace the evolution of

fire-arms in the ancient India. There is evidence to show that agni

(fire) was praised for vanquishing an enemy. The Arthava Veda shows

the employment of fire-arms with lead shots. The Aitareya Brahmana

describes an arrow with fire at its tip. In the Mahabharata and

Ramayana, the employment of agnyastras is frequently mentioned, and

this deserves careful examination in the light of other important

terms like ayah, kanapa and tula-guda.

The agnicurna or gunpowder was composed of 4 to 6 parts of saltpetre,

one part of sulphur, and one part of charcoal of arka, sruhi and

other trees burnt in a pit and reduced to powder. Here is certain

evidence of the ancient rockets giving place to actual guns in

warfare. From the description of the composition of gunpowder, the

composition of the Sukraniti can be dated at the pre-Gupta age.

(source:

War in Ancient India - By V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar 1944.

p. 103 -105).

Bow and Arrow:

In the words of H. H. Wilson:

"the Hindus cultivated archery most

assiduously and were very Parthians in the use of the bow on

horse-back."

One feature of this weapon was that it could be handled

by all the four classes of warriors.

Frescos on the Angkor Wat depict scenes from the Hindu epics

Mahabharata and Ramayana, showing Kshatriyas engaged in war.

For more refer to chapter on

Greater India: Suvarnabhumi and

Sacred

Angkor

Other Weapons:

The Bindipala and the nine following are minor weapons of this

class. Probably this was a heavy club which had a broad and bent

tail end, measuring one cubit in length. It was to be used with the

left foot of the warrior placed in front. The various uses of this

weapon were cutting, hitting, striking and breaking. It was like a

kunta but with a big blade. It was used by the Asuras in their fight

with Kartavirya Arjuna.

The Nalika is a hand gun or musket rightly piercing the mark. It was

straight in form and hollow inside. It discharged darts if ignited.

As has been already said, Sukracarya speaks of two kinds of nalika,

one big and the other small. The small one, with a little hole at

the end, measured sixty angulas (ie. distance between the thumb and

the little finger) dotted with several spots at the muzzle end.

Through the touch hole or at its breach which contained wood, fire

was conveyed to the charge. It was generally used by foot-soldiers.

But the big gun had no wood at the breach and was so heavy that it

had to be conveyed in carts. The balls were made of iron, lead or

other material. Kamandaka uses the word nalika in the sense of

firing gun as a signal for the unwary king. Again in the Naisadha, a

work of the medieval period, Damayanti is compared to the two bows

of the god of love and goddess of love, and her two nostrils to the

two guns capable of throwing balls.

Thus there is clear evidence of the existence and use of firing guns

in India in very early times.

The Cakra, the next weapon in the category, is a circular disc with

a small opening in the middle. It was of three kinds of eight, six

and four spokes. It was used in five or six ways. It resembled the

quoid of the Sikhs today. Lord Vishnu is popularly addressed as

Sankha-cakra-gada-pani, that is having Sankha or conch, Cakra or

disc, and Gada or mace in three of his four hands.The various uses

of a disc were felling, whirling, rending, breaking, severing, and

cutting. It is one of the instruments peculiar to Lord Vishnu.

Kautalya speaks of it as a movable machine. The Cakra belongs to the

category of a missile. According to the Vamanapurana, the Cakra has

lustrous and sharp edges.

The Tomara is another weapon of war frequently mentioned in all

kinds of warfare. It was of two kinds, an iron club (sarvayasam) and

a javelin. . According to the Agni Purana it was to be with the help

of an arrow of straight feathers, and was powerful in dealing blows

to the eyes and hands of an enemy.

The Dantakanta, is another weapon of war, perhaps the shape of a

tooth, made of metal, of strong handle and a straight blade. It had

two movements.

The Pasa, which is a noose killing the enemy at one stroke, of two

or tree ropes used as a weapon attributed to the god Varuna. It was

triangular in shape and embellished with balls of lead. It was

associated with three kinds of movements. In the Agni Purana are

described eleven ways of turning it to one's own advantage by

dexterity of hand.

The Masundi, was probably an eight sided cudgel. It was furnished

with a broad and strong handle. It apparently comes from the

root-meaning to cleave or break into pieces, and perhaps akin to the

Musala.

All these and more found used in one battle or another both in the

Mahabharata and the Ramayana.

Amukta Weapons

The first of the Amukta weapons was the Vajra or the thunderbolt.

The origin of this weapon is given in the Rirthayatra portion of the

Mahabharata. It was made out of the backbone of the Rishi Dadhici

which was freely given by him to Indra. Originally perhaps it had

six sides and made a terrible noise when hurled.

-

The Parasu is the battle-axe attributed to Parasu-rama, of great

fame. Its blade was made of steel and it had a wooden handle. There

were six ways of manipulating it to one's own advantage.

-

The Gada is a heavy rod of iron with one hundred spikes on the top.

One of the four cubits was able to destroy elephants and rocks. It

could be handled in twenty different ways. By means of gun powder it

could be used as a projectile weapon of war. Its principal use was

to strike the enemy either from a raised place or from both sides

and strike terror into the enemy especially of the Gomutra array.

-

The Mudgara was a staff in the shape of a hammer. It was used to

break heavy stones and rocks. This is again a movable machine

according to Kautalya.

-

The Sira was a bucket-like instrument curved on both sides and with

a wide opening made of iron. It was as long as a man's height. The

Pattisa is a razor like weapon.

-

The Sataghni, literally means that which had the power of killing a

hundred at a time. It looked like a Gada and is said to be four

cubits in length. It is generally identified with modern cannon and

hence was a projectile weapon of war.

It was generally placed on the walls of a fort and is included among

the movable machines by Kautalya.

-

Asi or the Swords - The best sword measured fifty inches. They were

usually made of Pindara iron found in the Jangala country, black

iron in the Anupa, white iron in the Sataharana, gold colored in the

Kalinga, oily iron in the Kambhoja, blue-colored in Gujarat,

grey-colored in the Maharashtra and reddish white in Karnataka. The

aSi si also known as Nistrimsa, Visamana, Khadga, Tiksnadhara,

Durasada, Srigarbha, Vijaya and Dharmamula, meaning respectively

cruel, fearful, powerful, fiery, unassailable, affording wealth,

giving victory, and the source of maintaining dharma. And these are

generally the characteristics of a sword.

It was commonly worn on the left side and was associated with

thirty-two different movements. It measured 50 thumbs in length and

four inches in width. In the Santi-parva (166,3 ff; 82 ff). Bhisma

being asked as to which weapon in his opinion was the best for all

kinds of fighting, replies that the sword is the foremost among arms

(agryah praharananam), but the bow is first (adyam).

B.K. Sarkar says that the secret of manufacturing the so-called

Damascus blade was learnt by the Saracens from the Persians, who, in

their turn, had learnt it from the Hindus. Early Arabic literature

provides us with a curious illustration of the esteem with which

Indian swords were looked upon in Western Asia.

An early Arabic

poet, Hellal, describing the flight of the Hemyarites, says:

"But

they fled under its (ie. the clouds) small hail of arrows quickly,

whilst hard Indian swords were penetrating them." and again: "He

died and we inherited him; one old wide (cuirass) and a bright

Indian (sword) with a long shoulder-belt."

(Hindu Achievements in

Exact Science - By B. K. Sarkar p. 45).

Note: Hindus made the best swords in the ancient world, they

discovered the process of making Ukku steel, called Damascus steel

by the rest of the world (Damas meaning water to the Arabs, because

of the watery designs on the blade). These were the best swords in

the ancient world, the strongest and the sharpest, sharper even than

Japanese katanas. Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Persians, Turks, and

Chinese imported it.

The original Damascus steel - the world's first

high-carbon steel - was a product of India known as wootz. Wootz is

the English for ukku in Kannada and Telugu, meaning steel. Indian

steel was used for making swords and armor in Persia and Arabia in

ancient times. Ktesias at the court of Persia (5th c BC) mentions

two swords made of Indian steel which the Persian king presented

him. The pre-Islamic Arab word for sword is 'muhannad' meaning from

Hind. So famous were they that the Arabic word for sword was Hindvi

- from Hind.

Wootz was produced by carburizing chips of wrought iron in a closed

crucible process.

"Wrought iron, wood and carbonaceous matter was

placed in a crucible and heated in a current of hot air till the

iron became red hot and plastic. It was then allowed to cool very

slowly (about 24 hours) until it absorbed a fixed amount of carbon,

generally 1.2 to 1.8 per cent," said eminent metallurgist Prof.

T.R.

Anantharaman, who taught at Banares Hindu University, Varanasi.

"When forged into a blade, the carbides in the steel formed a

visible pattern on the surface."

To the sixth century Arab poet Aus

b. Hajr the pattern appeared described 'as if it were the trail of

small black ants that had trekked over the steel while it was still

soft'. In the early 1800s, Europeans tried their hand at reproducing

wootz on an industrial scale. Michael Faraday, the great

experimenter and son of a blacksmith, tried to duplicate the steel

by alloying iron with a variety of metals but failed.

Some

scientists were successful in forging wootz but they still were not

able to reproduce its characteristics, like the watery mark.

"Scientists believe that some other micro-addition went into it,"

said Anantharaman.

"That is why the separation of carbide takes

place so beautifully and geometrically."

The crucible process could have originated in south India and the

finest steel was from the land of Cheras, said K. Rajan, associate

professor of archaeology at Tamil University, Thanjavur, who

explored a 1st century AD trade centre at Kodumanal near Coimbatore.

Rajan's excavations revealed an industrial economy at Kodumanal.

Pillar of strength The rustless wonder called the Iron Pillar near

the Qutb Minar at Mehrauli in Delhi did not attract the attention of

scientists till the second quarter of the 19th century.

The

inscription refers to a ruler named Chandra, who had conquered the Vangas and Vahlikas, and the breeze of whose valour still perfumed

the southern ocean. "The king who answers the description is none

but Samudragupta, the real founder of the Gupta empire," said Prof.

T.R. Anantharaman, who has authored The Rustless Wonder. Zinc

metallurgy travelled from India to China and from there to Europe.

As late as 1735, professional chemists in Europe believed that zinc

could not be reduced to metal except in the presence of copper.

The

alchemical texts of the mediaeval period show that the tradition was

live in India. In 1738, William Champion established the Bristol

process to produce metallic zinc in commercial quantities and got a

patent for it. Interestingly, the mediaeval alchemical text Rasaratnasamucchaya describes the same process, down to adding 1.5

per cent common salt to the ore.

(source:

Saladin's sword - By The Week - June 24, 2001 -

http://netinfo.hypermart.net/telingsteel.htm).

Artillery - India Taught Europe

Artillery was introduced into Europe by the Roma (Gypsies), who

were none else than the Jats and Rajputs of India.

This has been revealed in a study by a reputed linguist, Weer

Rajendra Rishi, after an extensive tour of Roma camps in Europe.

He explains that the Romas, who are the Gypsies of Europe, also

taught the use of artillery to Europeans. These Roma belonged to the

Jat and Rajput clans who left India during the invasions by Mohamud

Ghaznavi and Mohammad Ghori between the 10th and 12th centuries of

the Christian era.

He says the use of artillery was known in Asia, notably in India,

from time immemorial, while it was introduced to the Europeans much

later.

Mr. Rishi reveals that the Roma had helped different countries of

Europe in making artillery.

“Evidence of this is given as early as

1496 by a mandate of that date granted by Wadislas, King of Hungary,

wherein it is said that Thomas Polgar, chief of 25 tents of

wandering Gypsies had, with his people, made at Funfkirchen

musket-balls and other ammunition for Bishop Sigismond.

“In 1546

when the English were holding Boulogne against the French the latter

took the help of two experienced Romas of Hungary to make great

number of cannons of greater caliber than earlier guns. The

Hungarian Roma of the 16th century possessed fuller knowledge of

fabricating artillery than the races of Western Europe.

There were also records that the Roma were employed as soldiers by

some countries of Europe. Dr. W. R. Rishi, is the author of the

book, Roma - The Panjabi Emigrants in Europe, Central and Middle

Asia, the USSR, and the Americas - published 1976. Mr. Rishi is a

well-known linguist of India and was awarded the honour of 'Padmashri'

by the President of India in 1970 for his contributions in the field

of linguistics. He is also the Founder Director of the Indian

Institute of Romani Studies.

(source: Diamonds, Mechanism, Weapons of War, Yoga Sutras - By G. R. Josyer. p. 179-182).

Indian Armour

To conclude with the words of Sir George Birdwood:

" For a variety, extent, and gorgeousness, and ethnological and

artistic value, no such collection of Indian arms exists in this

country (England) as that belonging to the Prince of Wales. It

represents the armorer's art in every province of India, from the

rude spear of the savage Nicobar islanders to the costly damascened,

sculptured, and jewelled swords, and shields, spears, daggers, and

match-locks of Kashmir, Kutch and Vizianagaram. The most striking

object in the collection is a suit of armor made entirely of the

horny scales of the Indian armadillo, or pangolin, encrusted with

gold, and turquoise, and garnets."

(source: The Industrial Arts of India pp. 171-2).

Back to Contents

Martial Arts -

Fighting without weapons

Fighting without weapons was a specialty of the Ksatreya (caste of

Ancient India) and foot soldier alike.

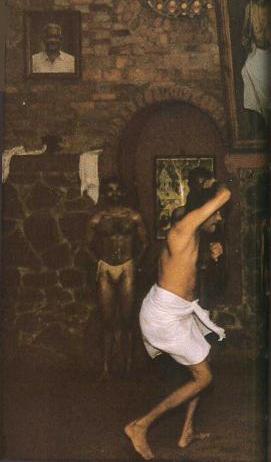

Danger and Divinity: Originating at least 1,300 years ago, India's

Kalaripayit is the oldest martial art taught today.

It is also one

of the most potentially violent.

Weaponless but nimble, a karaipayit

master displays for his students how to meet the attack of an armed

opponent.

Watch

Kalari Martial Arts and

Silambam Martial Arts videos

"Fighting without weapons was a specialty of the Ksatreya (caste of

Ancient India) and foot soldier alike. For the Ksatreya it was simply

part and parcel of their all around training, but for the lowly

peasant it was essential. We read in the Vedas of men unable to

afford armor who bound their heads with turbans called Usnisa to

protect themselves from sword and axe blows.

"Fighting on foot for a Ksatreya was necessary in case he was

unseated from his chariot or horse and found himself without

weapons. Although the high ethical code of the Ksatreya forbid

anyone but another Ksatreya from attacking him, doubtless such

morals were not always observed, and when faced with an unscrupulous

opponent, the Ksatreya needed to be able to defend himself, and

developed, therefore, a very effective form of hand-to-hand combat

that combined techniques of wrestling, throws, and hand strikes.

Tactics and evasion were formulated that were later passed on to

successive generations. This skill was called Vajramukhti, a name

meaning "thunderbolt closed - or clasped - hands." The tile

Vajramukti referred to the usage of the hands in a manner as

powerful as the vajra maces of traditional warfare. Vajramukti was

practiced in peacetime by means of regular physical training

sessions and these utilized sequences of attack and defense

technically termed in Sanskrit nata."

Kalaripayattu, literally “the way of the battlefield,” still

survives in Kerala, where it is often dedicated to Mahakali. The

Kalari grounds are usually situated near a temple, and the pupils,

after having touched the feet of the master, salute the ancestors

and bow down to the Goddess, begin the lesson. Kalari trainings have

been codified for over 3000 years and nothing much has changed.

The warming up is essential and demands great suppleness. Each

movement is repeated several times, facing north, east, south and

west, till perfect loosening is achieved. The young pupils pass on

to the handling of weapons, starting with the “Silambam”, a short

stick made of extremely hard wood, which in the olden times could

effectively deal with swords. The blows are hard and the parade must

be fast and precise, to avoid being hit on the fingers!

They

continue with the swords, heavy, and dangerous, even though they are

not sharpened any more, as they are used. Without guard or any kind

of body protection; they whirl, jump and parry, in an impressive

ballet. Young, fearless girls fight with enormous knives, bigger

than their arms and the clash of irons is echoed in the ground. The

session ends with the big canes, favorite weapons of the Buddhist

traveler monks, which they used during their long journey towards

China to scare away attackers.

The “Urimi” is the most extraordinary weapon of Kalari, unique in

the world. This double-edged flexible sword which the old-time

masters used to wrap around the waist to keep coiled in one hand, to

suddenly whip at the opponent and inflict mortal blows, is hardly

used today in trainings, for it is much too dangerous.

This indigenous martial arts, under the name of Kalari or

Kalaripayit exists only in South India today. Kalarippayat is said

to be the world's original martial art. Originating at least 1,300

years ago, India's Kalaripayit is the oldest martial art taught

today. It is also the most potentially violent, because students

advance from unarmed combat to the use of swords, sharpened flexible

metal lashes, and peculiar three-bladed daggers.

More than 2,000

years old, it was developed by warriors of the Cheras kingdom in

Kerala. Training followed strict rituals and guidelines. The

entrance to the 14 m-by-7 m arena, or kalari, faced east and had a

bare earth floor. Fighters took Shiva and Shakti, the god and

goddess of power, as their deities. From unarmed kicks and punches,

kalarippayat warriors would graduate to sticks, swords, spears and

daggers and study the marmas—the 107 vital spots on the human body

where a blow can kill. Training was conducted in secret, the lethal

warriors unleashed as a surprise weapon against the enemies of

Cheras.

Father and founder of Zen Buddhism (called C’han in China),

Boddidharma, a Brahmin born in Kacheepuram in Tamil Nadu, in 522

A.D. arrived at the courts of the Chinese Emperor Liang Nuti, of the

6th dynasty. He taught the Chinese monks Kalaripayattu, a very

ancient Indian martial art, so that they could defend

themselves

against the frequent attacks of bandits. In time, the monks became

famous all over China as experts in bare-handed fighting, later

known as the Shaolin boxing art. themselves

against the frequent attacks of bandits. In time, the monks became

famous all over China as experts in bare-handed fighting, later

known as the Shaolin boxing art.

The

Shaolin temple which has been

handed back a few years ago by the communist Government to the C’han

Buddhist monks, inheritors of Boddhidharma’s spiritual and martial

teachings, by the present Chinese Government, is now open to

visitors. On one of the walls, a fresco can be seen, showing Indian

dark-skinned monks, teaching their lighter-skinned Chinese brothers

the art of bare-handed fighting.

On this painting are inscribed:

“Tenjiku Naranokaku” which means: “the fighting techniques to train

the body (which come) from India…”

Kalari payatt was banned by the British in 1793.

(source:

The Boddhisattva Warriors: The Origin, Inner Philosophy,

History and Symbolism of the Buddhist Martial Art Within India and

China - By Terence Dukes/ Shifu Nagaboshi Tomio p. 3 - 158-174 and

242.

A Western Journalist on India: a ferengi's columns - By

Francois Gautier Har-Anand Publications January 2001 ISBN 8124107955

p. 155-158).

Silambam – Indian Stick Fighting

The art Nillaikalakki Silambam was brought to the royal court

during

the reign of the Cheran, Cholan and Pandian emperors, once powerful

rulers of India.

Watch

Kalari Martial Arts and

Silambam Martial Arts videos

The art Nillaikalakki Silambam, which exists for more than five

thousand years, is an authentic art which starts with the stick

called Silambamboo (1.68 meters long). It originates from the Krunji

mountains of south India, and is as old as the Indian sub-continent

itself.

The natives called Narikuravar were using a staff called Silambamboo

as a weapon to defend themselves against wild animals, and also to

display their skill during their religious festivals. The Hindu

scholars and yogis who went to the Krunji mountains to meditate got

attracted by the display of this highly skilled spinning Silambamboo.

The art Nillaikalakki Silambam therefore became a part of the Hindu

scholars and yogis training, as they were taught by the Narikuravar.

They brought the art to the royal court during the reign of the

Cheran, Cholan and Pandian emperors, once powerful rulers of India.

(source:

Silamban – Indian Stick Fighting).

Back to Contents

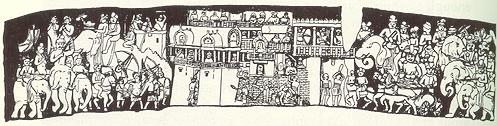

Army and Army

Divisions

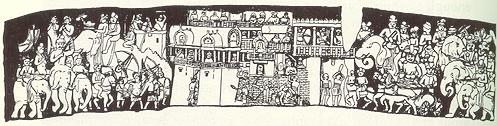

The Game of Chess and the Four-Fold Force

Owing to peculiar geographical features, with her vast plains

interspersed with forests, the ancient Indian States had to make

extensive use of mounted forces which comprised cavalry, chariots,

and elephants. This does not mean that infantry was neglected. Hindu

India possessed the classical fourfold force of chariots, elephants,

horsemen, and infantry, collectively known as the Caturangabala.

Students also know that the old game of chess also goes by the name

of Caturanga. Chess is a game of war, and in each game there are a

king, a councilor,

two elephants, two horses, two chariots, and

eight foot-soldiers. From the references to this game in the Rg Veda

and the Atharva Veda and in the Buddhists and Jaina books, it must

have been very popular in ancient India. The Persian term Chatrang

and the Arabic Shatrang are forms of the Sanskrit Chaturanga. two elephants, two horses, two chariots, and

eight foot-soldiers. From the references to this game in the Rg Veda

and the Atharva Veda and in the Buddhists and Jaina books, it must

have been very popular in ancient India. The Persian term Chatrang

and the Arabic Shatrang are forms of the Sanskrit Chaturanga.

The famous epic Mahabharata narrates an incidence where a game

called Chaturang was played between two groups of warring cousins.

In some form or the other, the game continued till it evolved into

chess.

H.J.R. Murray, in his work titled “A History of Chess”, has

concluded that,

“chess is a descendant of an Indian game played in

the 7th century AD”. The Encyclopedia Britannica states that “we

find the best authorities agreeing that chess existed in India

before it is known to have been played anywhere else.”

On the whole the board is 8 X 8 squares. According to Taylor, the

game of chess was the invention of some Hindu who devised a game of

war with the astapada board as his field of battle. From the

reference to the game in the Rig Veda and the Arthava Veda and in

the Buddhist and Jaina books, it must have been very popular in

ancient India. It is to be noted that the relative values of the

chess pieces were analogous to or identical with the relative values

of different arms as laid down by Kautalya, Sukra, and Vaisampayana.

The organization of the Indian army which came to be known as

Caturanga, both in epic Sanskrit and Pali literature, was based on

the ancient game.

The Chariots

Chariots were used in warfare from very remote times.

There are many references to chariots in the Samhitas and in the

Brahmanas. The chariot was an indispensable instrument of war in the

days of the Vedas, and on its possession depended victory. In the Rg

Veda there is a hymn addressed to the war chariot: ' Lord of the

wood, be firm and strong in body: be bearing as a brave victorious

hero.

Show forth thy strength, compact with straps of leather and

let thy rider win all spoils of battle.' Chariots were of different

types and materials. In the Ramayana and the Mahabharata their use

is largely in evidence. Each chariot was marked off by its ensign

and banner. Besides flags, umbrellas (chattra, atapatra), and fans

were a part of the paraphernalia of the war chariot.

Sukra mentions

an awe-inspiring chariot of iron with swift-moving wheels, provided

with good seats for the warriors and a seat in the middle for the

charioteer; the chariot was also equipped with all kinds of

offensive and defensive weapons.

Warrior Arjuna with Krishna - driving the chariot in the epic The

Mahabharata.

The Bhagavad Gita has influenced great Americans from Thoreau to

Oppenheimer.

Its message of letting go of the fruits of one’s

actions is just as relevant today as it was when it was first

written more than two millennia ago.

The conception of the sun-god in Indian tales is of value to the

student of ancient Indian military history. The idea is that the

sun-god wants to destroy darkness. Therefore he dons a lustrous

armor and marching in his swift flying chariot drawn by seven

powerful steads, Aruna (dawn) being his charioteer. The whole image

presents a life-like portrait of the military dress as well as the

march against an enemy.

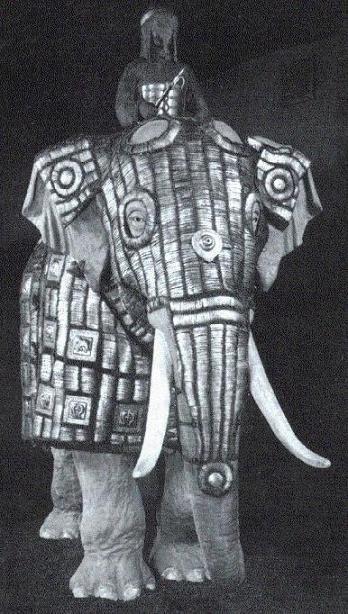

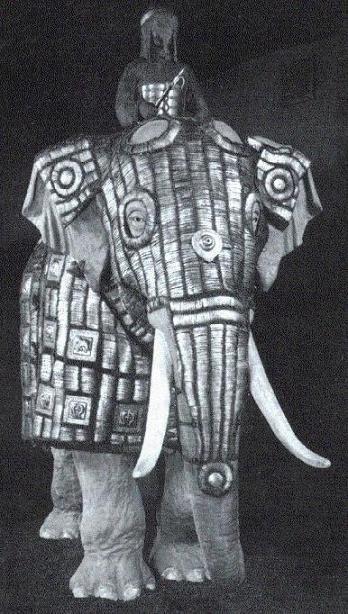

Elephants

The next important force of war consisted of elephants.

The numerous representations of the animal on coins and in

architectural sculptural works from Gandhara to Ramesvaram as well

as bronze figures in Indonesia are an indication of the esteem in

which it was held by the ancient Indians, clearly on account of its

usefulness.

An Elephant Armour: An important force of war consisted of

elephants.

There is a reference in the Rg Veda to two elephants bending their

heads and rushing together against the enemy, which is a fairly

early reference to the animal being used in war. By the time of the

Yajur Veda Samhita the art of training elephants had become common.

The Arthasastra mentions a special officer of the State for the care

of elephants and lays down his duties.

Megasthenes explains how the

elephants were hunted, and how their distempers were cured by simple

remedies such as cow's milk for eye-disease and pig's fat for sores.

A Jataka story throws some light on how fire-weapons were used in

ancient India.

"Once a king mounted on an elephant and led an attack

on the city of Benares. The soldiers who offered defenses from

within the city gates discharged a shower of missiles against the

enemy at which the elephant was frightened a little."

The use of

burning naphtha balls thrown against on rushing elephants to

frighten them and make them turn back on their own side, is

mentioned by early Mohammadan historians as a feature of the warfare

between the Rajputs and the Turkish invaders from the North-West.

(Elliot and Dowson, vol. I).

Cavalry

We hear from the Kautaliya and Megasthenes that

there was a

well-organized and efficient cavalry force in the army of Chandragupta.

In the ArthaVeda we hear of dust-raising horsemen.

We hear from the Kautaliya and Megasthenes that there was a

well-organized and efficient cavalry force in the army of

Chandragupta. In the ArthaVeda we hear of dust-raising horsemen. In

this connection it is interesting to consider the oft-repeated

statement that horses are non-Indian. It is not the whole truth.

They were known to the Asuras of Vedic literature. There is a legend

narrated in the third book of the Hariharacaturanga (though this is

work of the late 12th century A.D., the tradition recorded is very

ancient). In the epoch of the epics and the Arthasastra, we find

that the cavalry occupied as important a place in the army as any

other division.

Megasthenes corroborates the evidence of the Arthasastra. There was

a special department in the State for the cavalry. The horses of the

State were provided with stables and placed under the care of good

grooms and syces. There were several trained horsemen who could jump

forward and arrest the speed of galloping horses. But the majority

of them rode their horses with bit and bridle. When horses became

ungovernable they were placed in the hands of professional trainers

who made the animals gallop round in small circles. In selecting

horses of war, their age, strength, and size were taken into

account.

We may remark in passing that Abhimanyu's horses were only

three years old.

How important the science of horses was to the ancient Indians is

best seen from the Laksanaprakasa which quotes from several

important old authorities some of which are probably lost to us.

Among them are the Asvayurveda and Asvasastra, the former attributed

to Jayadeva and the latter to Nakula. Both the Puranas and the epics

agree that the horses of the Sindhu and Kamboja regions were the

finest breed and that the services of the Kambojas as cavalry

troopers were requisitioned in ancient wars.

In the Mahabharata war

the Kambojans (Cambodians) were enlisted. The steeds of Bahalika

were also highly esteemed. Horses had names and so did elephants.

Unlike the chariot horse, the cavalryman drove his animal with a

whip which was generally fixed to the wrist. This allowed his hand

free play. The cavalryman was armed with arrow or spear or sword. He

wore breastplate and turban (unsnisa). Worth noting is the fact that

horses were made to drink wine before actually marching to battle.

The tactical use of the cavalry was to break through the obstacles

on the way, to pursue the retreating enemy, to cover the flanks of

the army, to effect speedy communication with the various parts of

the army unobserved (bahutsara) and to pierce the enemy ranks from

the front to the rear. The cavalry was responsible, in a large

measure, for the safety and security of the army in entrenched

positions, forests or camps. It obstructed movements of supplies and

reinforcements to the enemy. In short, the cavalry was indispensable

in situations requiring quickness of movement.

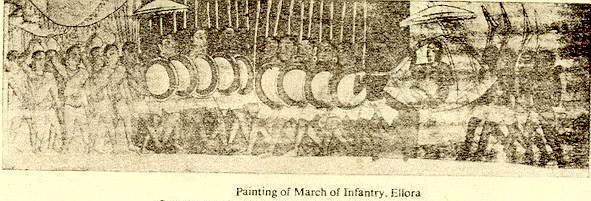

Infantry

The next important division of the army was the infantry, or

foot-soldier. The Arthasastra speaks of the infantry as a separate

army department under the charge of a special officer of the State.

This receives confirmation from Megasthenes statement. Besides the

maula or hereditary troops which formed a considerable portion of

the army, there were,

-

the bhrta or mercenaries

-

the sreni or soldiers

supplied by the different group and guild organizations

-

the mitra

or soldiers supplied by allies

-

the amitra or deserters from the

enemy ranks

-

the atavi recruited from forest tribes

According

to the Sukraniti and the Kamandakanitsara, the army was to be made

as imposing as possible to frighten the enemy by its size. The

Agni-purana says that victory ever attends the army where

foot-soldiers are numerically strong.

The Sukraniti also mentions that foot-soldiers possessed fire-arms

when they fought.

When these foot-soldiers equipped themselves for war

Arrian says

that,

'they carry a bow made of equal length with the man who bears

it. This they rest upon the ground and pressing against it and their

left foot, thus discharge the arrow having drawn the string

backwards: the shaft they use is little short of being three yards

long, and there is nothing which can resist an Indian Archer's shot

- neither shield nor breast-plate, nor any stronger defense if such

there be.'

In their left hand they carry bucklers made of undressed

ox-hide which are not so broad as those who carry them but are about

as long. If we turn to the ancient nations and especially the

ancient Egyptians we meet with almost a similar description.

The Commissariat

The Caturanaga was a classical division of the army accepted by

tradition. But in the epoch of the epic we hear of a Sadanga or the

six-fold army, including commissariat and admiralty. The use of

commissariat can be traced to the epic age. This belonged to the

category of administrative division of troops as against

the

combatant. We are told that this division of the army into two

categories was first seen in the battle of Mansikert (1071 A.D.) the

combatant. We are told that this division of the army into two

categories was first seen in the battle of Mansikert (1071 A.D.)

But, centuries before, the Indian army leaders had realized the

value of such a division. It is said that when the Pandava army

marched to Kurukshetra it was followed by 'carts and transport cars,

and all descriptions of vehicles, the treasury, weapons and machines

and physicians and surgeons, along with the few invalids that were

in the army and all those that were weak and powerless. This was

purely a civil department attached to the army. Care was also given

to wounded animals.

The numerous references in our authorities to the Commissariat

demonstrate beyond doubt that wars were planned methodically and

conducted systematically.

The Admiralty

The Admiralty as a department of the State may have been a creation

of Chandragupta but there is evidence to show that the use of ships

and boats was known to the people of the Rig Veda. In the following

passage we have reference to a vessel with a hundred oars.

"This

exploit you achieved, Asvins in the ocean, where there is nothing to

give support, nothing to rest upon, nothing to cling to, that you

brought Bhujya, sailing in a hundred-cared ship, to his father's

house." (refer to Naval warfare section).

Cartography

There is no special word in Sanskrit for a 'a map.' There is,

however, reason to believe that in ancient India a map or chart was

regarded as a citra or alekhya, i.e., 'a painting, a picture, a

delineation'. That maps were made in ancient India seems to be quite

clear from the evidence of the New History of the T'ang Dynasty

which gives an account of the Chinese general Wang Hiuen-tse's

exploits in India in the year 648 A.D.

With reference to the knowledge of map-making among the people of

India, especially the Dravidians of the South:

"The charts in use by the medieval navigators of the Indian Ocean -

Dravidas, Arabs, Persians, were equal in value, if not superior, to

the charts of the Mediterranean. Marco Polo (1498) found them in the

hands of his Indian pilot, and their nature is fully explained in

the Mohit or 'the Encyclopaedia of the Sea'"

Hindu Valor

The Hindus were declared the by the Greeks to be the bravest nation

they ever came in contact with. (source: History of India - by

Mountstuart Elphinstone p. 197).

It was the Hindu King of Magadha that struck terror in the

ever-victorious armies of Alexander.

Abul Fazal, the minister of Akbar, after admiring their noble

virtues, speaks of the valor of the Hindus in these terms:

“Their

character shines brightest in adversity. Their soldiers (Rajputs)

know to what it is to flee from the fields of battle, but when the

success of the combat becomes doubtful, they dismount from their

horses and throw away their lives in payment of the debt of valor.”

Francois Bernier, a 17th century traveler says that:

“The Rajputs

embrace each other when on the battlefields as if resolved to die.”

The Spartans, as is well known, dressed their hair on such

occasions. It is well known that when a Rajput becomes desperate, he

puts on garments of saffron color, which act, in technical language,

is called kesrian kasumal karna (donning saffron robes).

(source: Hindu Superiority - By Har Bilas Sarda p. 79 - 91).

Back to Contents

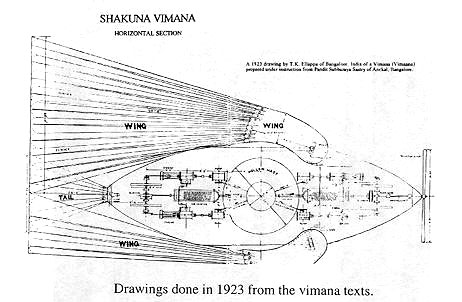

Aerial Warfare

“The ancient Hindus could navigate the air, and not only navigate

it, but fight battles in it like so many war-eagles combating for

the domination of the clouds. To be so perfect in aeronautics, they

must have known all the arts and sciences related to the science,

including the strata and

currents of the atmosphere, the relative

temperature, humidity, density and specific gravity of the various

gases...” currents of the atmosphere, the relative

temperature, humidity, density and specific gravity of the various

gases...”

~ Col. Henry S Olcott (1832 – 1907)

American author, attorney,

philosopher, and cofounder of the

Theosophical Society in a lecture

in Allahabad, in 1881.

"No question can be more interesting in the present circumstances of

the world than India’s contribution to the science of aeronautics.

There are numerous illustration in our vast Puranic and epic

literature to show how well and wonderfully the ancient Indians

conquered the air.

To glibly characterize everything found in this

literature as imaginary and summarily dismiss it as unreal has been

the practice of both Western and Eastern scholars until very

recently. The very idea indeed was ridiculed and people went so far

to assert that it was physically impossible for man to use flying

machines. But today what with balloons, airplanes…..”

Turning to Vedic literature, in one of the Brahmanas occurs the

concept of a ship that sails heavenwards. The ship is the Agnihotra

of which the Ahavaniya and Garhapatya fires represent the two sides

bound heavenward, and the steersman is the Agnihotrin who offers

milk to the three Agnis. Again in the still earlier Rg Veda Samhita

we read that the Asvins conveyed the rescued Bhujya safely by means

of winged ships. The latter may refer to the aerial navigation in

the earliest times.

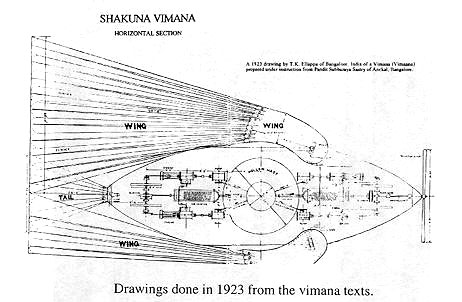

In the recently published Samarangana Sutradhara of Bhoja, a whole

chapter of about 230 stanzas is devoted to the principles of

construction underlying the various flying machines and other

engines used for military and other purposes.

The ancient Hindus could navigate the air, and not only navigate it,

but fight battles in it like so many war-eagles combating for the

domination of the clouds

The various advantages of using machines, especially flying ones,

are given elaborately. Special mention is made of their use at one’s

will and pleasure, of their uninterrupted movements, of their

strength and durability, in short of their capability to do in the

air all that is done on earth. Three movements are usually ascribed

to these machines, - ascending, cruising thousands of miles in

different directions in the atmosphere and lastly descending.

It is

said that in an aerial car one can mount up to Suryamandala, ‘solar

region’ and the Naksatra mandala (stellar region) and also travel

throughout the regions of air above the sea and the earth. These

cars are said to move so fast as to make a noise that could be heard

faintly from the ground. The evidence in its favor is overwhelming.

An aerial car is made of light, wood looking like a great bird with

a durable and well-formed body having mercury inside and fire at the

bottom. It had two resplendent wings, and is propelled by air. It

flies in the atmospheric regions for a great distance and carries

several persons along with it. The inside construction resembles

heaven created by Brahma himself.

Iron, copper, lead and other

metals are also used for these machines. All these show how far art

and science was developed in ancient India in this direction. Such

elaborate description ought to meet the criticism that the vimanas

and similar aerial vehicles mentioned in ancient Indian literature

should be relegated to the region of myth.

The ancient writers could certainly make a distinction between the

mythical which they designated as daiva and the actual aerial wars

designated as manusa. The ancient writers could certainly make a distinction between the

mythical which they designated as daiva and the actual aerial wars

designated as manusa.

After the great victory of Rama over Lanka, Vibhisana presented him

with the Puspaka vimana which was furnished with windows,

apartments, and excellent seats. It was capable of accommodating all

the vanaras besides Rama, Sita and Lakshman. Again in the

Vikramaurvaisya, we are told that king Puraravas rode in an aerial

car to rescue Urvasi in pursuit of the Danava who was carrying her

away.

Similarly in the Uttararamacarita in the flight between Lava

and Candraketu (Act VI) a number of aerial cars are mentioned as

bearing celestial spectators. There is a statement in the

Harsacarita of Yavanas being acquainted with aerial machines. The

Tamil work Jivakacintamani refers to Jivaka flying through the air.

Kathasaritsagara refers to highly talented woodworkers called

Rajyadhara and Pranadhara. The former was so skilled in mechanical

contrivances that he could make ocean crossing chariots. And the

latter manufactured a flying chariot to carry a thousand passengers

in the air. These chariots were stated to be as fast as thought

itself.

(source:

India Through The Ages: History, Art Culture and Religion -

By G. Kuppuram p. 532-533).

For more information refer to

Vymanika Shashtra.

Back to Contents

|

armies to the

north. The route lay through the Dakhan plateau, the Kalinga, Malva,

and the Ganga. Perhaps it was the ancient Daksinapatha route known

to history from the epoch of the Rg Veda Samhita.

armies to the

north. The route lay through the Dakhan plateau, the Kalinga, Malva,

and the Ganga. Perhaps it was the ancient Daksinapatha route known

to history from the epoch of the Rg Veda Samhita.

Gustav Oppert (1836-1908) born in Hamburg, Germany, he taught

Sanskrit and comparative linguistics at the Presidency College,

Madras for 21 years. He was the Telugu translator to the Government

and Curator, Government Oriental Manuscript Library. Translated

Sukraniti, statecraft by an unknown author.

Gustav Oppert (1836-1908) born in Hamburg, Germany, he taught

Sanskrit and comparative linguistics at the Presidency College,

Madras for 21 years. He was the Telugu translator to the Government

and Curator, Government Oriental Manuscript Library. Translated

Sukraniti, statecraft by an unknown author.

themselves

against the frequent attacks of bandits. In time, the monks became

famous all over China as experts in bare-handed fighting, later

known as the Shaolin boxing art.

themselves

against the frequent attacks of bandits. In time, the monks became

famous all over China as experts in bare-handed fighting, later

known as the Shaolin boxing art.

two elephants, two horses, two chariots, and

eight foot-soldiers. From the references to this game in the Rg Veda

and the Atharva Veda and in the Buddhists and Jaina books, it must

have been very popular in ancient India. The Persian term Chatrang

and the Arabic Shatrang are forms of the Sanskrit Chaturanga.

two elephants, two horses, two chariots, and

eight foot-soldiers. From the references to this game in the Rg Veda

and the Atharva Veda and in the Buddhists and Jaina books, it must

have been very popular in ancient India. The Persian term Chatrang

and the Arabic Shatrang are forms of the Sanskrit Chaturanga.

the

combatant. We are told that this division of the army into two

categories was first seen in the battle of Mansikert (1071 A.D.)

the

combatant. We are told that this division of the army into two

categories was first seen in the battle of Mansikert (1071 A.D.)

currents of the atmosphere, the relative

temperature, humidity, density and specific gravity of the various

gases...”

currents of the atmosphere, the relative

temperature, humidity, density and specific gravity of the various

gases...”

The ancient writers could certainly make a distinction between the

mythical which they designated as daiva and the actual aerial wars

designated as manusa.

The ancient writers could certainly make a distinction between the

mythical which they designated as daiva and the actual aerial wars

designated as manusa.