|

by John Major Jenkins from Alignment2012 Website

7 Wind provides a format for teaching

about the workings of the Mesoamerican Sacred Calendar. Because the

ancient calendar tradition is still alive in the highlands of

Guatemala, the details related here correspond with the practices of

the present day Quiché Maya. As such, this booklet is an educational

calendar. It serves as a focus for sharing the many related aspects

of the Quiché world, and offers the chance to track the sacred count

of days, in solidarity with the Quiché Maya.

The calendar tradition in the Yucatan

has suffered many adjustments and alterations since the conquest

and, although the traditions there provide other valuable

ethnographic material, any field work data from the Yucatan must

take into account the post-conquest distortions. So the search

unmistakably points to the Quiché Maya. A brief introduction to

Quiché history and culture will help put into context the specific

calendar practices discussed in the remaining sections of 7 Wind.

Strategically situated on established migration and trade routes between the old Toltec cities of Central Mexico and the Classic Maya cities of the Yucatan, Tulan Zuyua was also near the mouth of the Usamacinta river, which leads inland through Chiapas and into the highlands of Guatemala. Quiché documents relate that 13 separate groups of Toltec priest-warriors migrated to the highlands around the year 1200 A.D.

The Quiché people arose and eventually grew to dominate the other Mayan groups of the area - the Cakchiquel, Ixil, Mam, and the Tzutuhil. Quiché civilization reached its apex just before the conquest, circa 1450, but ultimately fell to the conquistador Pedro Alvarado in 1524.

During the conquest, the Cakchiquel

leaders Nine Dog and Three Deer were executed and the Tzutuhil chief

Tecun Uman is said to have been killed in a hand to hand duel with

Alvarado on the shores of Lake Atitlan. The last Quiché capital was

at K'umarcaaj, near Santa Cruz del Quiché. The ruins are now known

as Utatlan, and are still the focus of shrine ceremonies and

rituals.

Momostenango will be of particular interest to us, because that area seems to have enjoyed a certain autonomy over the centuries, as well as a seeming immunity from ongoing attempts to destroy native culture. The major reason for this goes back to the conquest, when Quiché patrilineage leaders were given privileged positions in the local Momostecan community. Since then, a continuous experiment of shared government between the Quiché and the Spaniards has taken place, along with a blending of Christian and Indigenous symbology, enabling the essential ancient traditions to survive.

This is not to say that the process has been without oppression and revolt. Indeed, periodic "development programs" by Catholic catequistas and, more recently, the Evangelicals have threatened the continuity of the calendar traditions. But for various reasons Momostenango has survived the worst, even emerging from the genocidal government tactics of the 1980's relatively unscathed. As a result of this autonomy, and setting it apart from the many other Mayan towns in the highlands, Momostenango retains a complex practice of visiting local earth-shrines on specific days in the sacred count.

These practices have been recorded in the excellent book Time and the Highland Maya, by Barbara Tedlock. Provided with this valuable information, we can explore the meaning of Mayan time and earth-worship. What a wonderful place Momostenango must be - where calendar-priests of all kinds, from different towns even, climb the sacred mountains to burn copal and pray to Day-Gods, the Year-Bearer, and to Nantat, the ancestors.

It seems that the entire geography

surrounding Momostenango has been made sacred, by regular ceremonies

at family, community, and regional earth-shrines. Indeed,

Momostenango is a Nahuatl term meaning "place of the shrines." It is

also the place where the most famous indigenous festival timed by

the tzolkin calendar is held: the 8 Monkey festival.

Perhaps they were descendants of the

Olmecs, who are known to have had towns in Guatemala -

giant Olmec

heads can still be found in the central park of El Baul on the

pacific slopes. Some of this we can only speculate about, but one

thing is for certain: The ancient tzolkin count has survived in the

mountains of Guatemala.

The Maya have admittedly undergone many

changes — migrations, invasions and wars have come and gone in the

vast expanse of time since the Sacred Count first emerged. And now

we find ourselves nearing the end of a Great Cycle of time as

conceived by the ancient Maya. Perhaps it is time that we sat down

to counsel with the Quiché Maya —"the last holders of the torch."

This large period of time was called the Calendar Round. The framework of days created by combining the tzolkin and haab serves many purposes, and this is why it is incredible. The problem with our calendar, the Gregorian calendar, is that it is only used to track time! The Mayan tzolkin/haab system was used to track astronomical cycles, as well as agricultural and human cycles. Because of this, it provides a model in which human life is mirrored by the celestial cycles of Moon, Venus, Mars and certain stars. As they say in the Far East, the microcosm reflects the macrocosm.

This principle became a distinguishing

feature of the philosophies of the Far East, as well as in the

religions of Native America. Throughout the various aspects of

Quiché culture, we find this unifying principle in operation. It

indicates an attitude of "learning from nature," which in turn leads

to an understanding of human nature. And what is it to be human? The

skywatchers of ancient Central America may have asked themselves

that same question many times. And it is difficult to reconcile this

paradox, however true it rings: that we come from stars and spring

from the earth, and the greatest gifts of life are simply a mystery.

As such, it provides a metaphysical

model for understanding the interface of subjective and objective

reality. In light of our present environmental crisis, which springs

from an incomplete understanding of the relationship of mind to

nature, the Mayan sacred calendar offers a much needed new paradigm.

(Actually, it is only "new" to us.) When we look at all of its

multiple meanings, we discover that it is much more than a calendar.

This is evident for two reasons. First,

they knew that 1507 true solar years was equal to 1508 haab. Second,

with their Long Count calendar they could calculate solstice and

equinox positions for many thousands of years into the future. This

explains how they could have placed the end date of the Long Count

Great Cycle exactly on the winter solstice of 2012 A.D. This is

truly phenomenal considering that the Long Count was conceived

around 300 B.C.!

The beginning of the Venus cycle was

figured to be when it emerges as morning-star. This occurs about

every 584 days. This 584-day cycle meshes with the 260-day tzolkin

in such a way that Venus always emerges on 5 possible day-signs.

Mythologies developed around these five day-signs. One of the

day-signs was the most significant, because it indicated the Venus morningstar appearance which synchronized all three cycles of

tzolkin, haab and Venus, to begin a new Venus Round period. This day

was 1 Ahau, the Sacred Day of Venus.

The ancient

Popol Vuh of the Quiché Maya

relates the adventures of the Hero twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque as

they battle with the Lords of Xibalba. Their adventures are actually

metaphors for the movement of Venus through 5 cycles. And the Aztec

god Quetzalcoatl journeys through the underworld and ultimately

ascends to become the morningstar Venus.

In such a practice, the multiple interpretations of the day-signs are considered in determining the reading. The expanded meanings are derived through linguistic associations - through word puns and rhymes. So the one-word translations that follow are only sketches of the full meanings of the day-signs, as understood by the Quiché:

Alternative meanings:

These are similar to the Classic Maya meanings. Strangely, the geomantic journey implied from this sequence ends with the day-sign Ahau, which I have translated as birth. The reason for supposing that Ahau can be equated with birth is because 1 Ahau, as the Sacred Day of Venus, designates the conjunction of the three cycles of Venus, haab and tzolkin, and the beginning of a new Venus Round period of 104 haab.

Needless to say, beginnings are related

to birth. The image gains graphic support when we realize that Venus

emerges as morningstar on this date, being visibly "shot forth" or

"born" from the morning sun. Also, the Yucatec Maya translation of

Ahau is "marksman" or "blowgunner." That the 20-day sequence ends

with Birth refers to the Mayan concept of time as not only cyclic,

but as leading to something new. Mayan time encodes an unfolding

type of cycle, a spiral growth of human and cosmic proportions -

something beyond the scope of circular "clock" time.

On the second day it is usually visible as a sliver in the west right around sunset. Counting forward, the moon increases in phase for 13 days. Each day represents a distinct phase during the moon's growth to fullness. By day 13, for all apparent purposes, it is full - the moon actually appears to be full for 2 to 3 days. In this way 13 symbolizes the growth of the moon from new to full.

Furthermore, the phases actually

indicate the three-way relationship between the earth, sun and moon,

something that is not immediately apparent. In a similar way, the

365-day "solar" cycle is in fact the "earth" cycle of the earth

around the sun. If we think through the apparently obvious from

different perspectives, the paradoxical secrets of nature are

revealed.

The earliest tzolkin date known was found at an Olmec site and corresponds with 679 B.C. Another explanation is that the 260-day cycle is derived from early attempts to track the movements of Venus and the sun. One explanation given among contemporary Quiché daykeepers is that it corresponds to the 260-day period of human gestation. This equals approximately nine months, and is therefore one reason for calling the tzolkin a "lunar" calendar.

The origins of the sacred calendar are

ultimately shrouded in mystery. In my studies I have been mainly

concerned with searching for the essence of its incredible

qualities. Above all, the tzolkin has many different uses, or what I

call "multiple meanings." This very fact may be why the number 260

was considered to be sacred.

It utilizes a leap year every four

years. And to adjust for a further discrepancy, it ignores leap

years if the year is divisible by 100 but not by 400. Thus the years

1600 and 2000 are leap years, but 1700, 1800, 1900 and 2100 are not.

The Quiché still use the haab count, though it doesn't seem to have as much importance as the tzolkin count. It just may be that the intervention of the Gregorian calendar replaced the haab as a useful "civil" calendar. The difference is that the haab doesn't recognize leap years, and therefore preserves a repeating count of 365 days. This is important so that its mythological relationship to the tzolkin stays consistent. Also, the New Years Day of the haab is not January 1st.

The New Years Day celebrated by the Quiché presently falls on Feb 26th. Many ceremonies occur in preparation for this event. Because the haab does not count leap-years, New Years Day falls back one day every four years. The eighteen months are named as follows:

The 19th month of 5 days is called

"Extra Days". This is a time when people stay at home, abstain from

sex and eat little. They are preparing for the entering of the next

year bearer. The month names may not be explicitely recollected at

the beginning of each uinal. Nevertheless, the first day of each

uinal is celebrated as an echo of the year bearer.

The year bearers represent the 4 directions, and correspond with the 4 sacred mountains around Momostenango. The 5 days of the "Extra Days" month leading up to the entering of the new year bearer are filled with anxious expectation, councils and talk of the qualities of the coming year bearer.

The 4 year bearers of the Quiché Maya are: Wind, Deer, Tooth, and Quake. The numbers associated with each year bearer increase by one every year (13 goes into 365 twenty-eight times with 1 left over). In this way, the year which begins on Feb. 26th, 1993 is 7 Wind. Wind is known as a very bravo year bearer, bringing violent rainstorms or else windstorms without rain.

On 1, 6 and 8 Wind days during a Wind

year, daykeepers ask that lightning, earthquakes and floods do not

destroy their homes. They also ask that negative emotions do not

attack themselves, their family, or their clients. The following

year, beginning on Feb 26th, 1994 is called 8 Deer. 8 Deer is a

special day for the Quiché, and it will be interesting to learn

whether the entering of this year bearer in '94 will entail any

special ceremonies.

The twenty-day month wheels in 7 Wind

all begin on Wind, and designate the 18 haab months. Because Wind is

regarded as a particularly violent year-bearer, it is only observed

on a few of the uinals, ones which begin with 1 Wind, 6 Wind and 8

Wind. These regular celebrations typically involve fireworks,

alcohol and shrine ceremonies.

Since then, New Years Day has fallen back over 200 days, so that in 1993 it occurs on February 26th. Or perhaps they made a change to coordinate New Years Day with a Venus rising - to synchronize the Calendar Round beginning with the Venus Round beginning.

At any rate, the Quiché New Years Day no doubt

originated from the Classic Maya New Years Day (300 A.D. - 900

A.D.), which, although no longer followed by any Mayan group, occurs

40 days after the Quiché New Year's. It won't be until the year 2217

that the Quiché New Year's corresponds with January 1st.

This is the first day

of the first haab month, First Lord. The first day of the second

haab month (Second Lord) falls on 1 Wind, and the next on 8 Wind, 2

Wind, 9 Wind, and so on. After 13 haab months are passed through, 7

Wind returns to initiate the 14th haab month (Trees) on November

13th. This is recognized by the Quiché as a "little New Year."

Wind will enter on the sacred mountain of west, Socop, on February 26th, 1993. The 5 days leading up to the entering of this year bearer are the 5 "unlucky" days, as the 6 Quake year leaves. Activity is curtailed, people stay at home and eat little. They especially abstain from sex and green vegetables.

On the day before the year bearer enters, what we would call New Years Eve, the daykeepers prepare for the impending celebration with prayers to the earth-god Mundo and the new year bearer, which is called by the Ixil Maya the mam. And the culture at large prepares for festivities and fireworks, usually beginning at midnight. But even after sunset on New Years Eve, it is recognized that the old year bearer has now left, and the new year bearer begins to stir.

Exactly at what point the day-sign's

influence begins is a matter of contention, even among the

daykeepers themselves. Some say it begins at sunrise, while others

insist it begins at midnight. An argument could be made for the

first stirrings of a day-sign at sunset of the previous day, or even

after the sun passes its zenith on the previous day. And yet a day

is generally considered over when the sun sets (the word Q'ij means

both day and sun). At any rate, the modern Quiché seem to time at

least some of their celebrations as the clock strikes 12, so to

speak.

The question of when this period begins depends upon which year bearer is considered to be the "senior" year bearer. When the number 1 rolls around to join with the senior year bearer, Calendar Round celebrations took place. Unfortunately, the present day Quiché have little interest in this large cycle, although they still vaguely acknowledge it.

We can reconstruct the Quiché Calendar Round based upon the fact that Deer is the senior year bearer of the Quiché (as well as for the Ixil Maya). A list of year bearers will help us locate when 1 Deer occurs as the year bearer:

The next Quiché Calendar Round begins on February 18th in the year 2026. This means that the present Calendar Round began on March 3rd, 1974. The Calendar Round cycle is useful when we begin to explore the larger planetary and eclipse cycles, and how the tzolkin/haab was originally intended to structure them.

For instance, the ancient Venus Round calendar is comprised of 2 consecutive Calendar Rounds. Twenty of these Venus Rounds equal thirteen conjunctions of Uranus and Neptune (there's that 20:13). Another example: The astronomical eclipse half-year is 173.3 days. This period of time indicates the interval between when eclipses can be expected to occur.

It just so happens that three of these eclipse half-years equal two tzolkins:

This is an aspect of the calendar that one rediscovers in ones

studies, although it is not directly applicable to the present day Quiché Maya.

The event is actually the culmination of months of preparation, in which the novice and his or her teacher practice counting the sacred days, and make offerings at local shrines. The teacher-daykeeper also begins to model for the novice, to demonstrate how to cast readings with tz'ite beans according to the sacred count of days. The preparatory "permission" days, leading to 8 Batz, are observed as follows:

Notice that 1 Storm and 1 Road are shared by both services.

During the 7 Wind year, 8 Batz occurs on September 23rd. So the series of permission days just related occur between May 22nd (1 Deer) and September 16th (1 Lizard). Yet this is not all. There are four levels of daykeepers among the Quiché people. First there are the common apprentices, whom we have been discussing and who for all practical purposes are in training. There are upwards of 10,000 of these common daykeepers among the Maya.

Next, there are perhaps 300 "patrilineage" priest-shamans, who speak and do readings for their own extended family or lineage. At the third level, there are the "canton" priest-shamans. They represent the 14 or so civil districts around Momostenango. Finally, two or three mother-fathers at the highest level are respected daykeepers, well versed in local myth and calendar lore.

These highest calendar-priests are experienced elders, male or female, and speak for the entire region. The amazing thing I am getting at is that initiation events for each of these levels are timed alongside the permission days related above. A three-tiered hierarchy is demonstrated; and each level is not mutually exclusive, but intricately interwoven. For example, the permission days related above pertain to the novice level. It consists of two separate phases, which also interlap. 1 Deer through 1 Road are called "washing for the mixing point." And 1 Storm through 1 Lizard are called "Washing for the work service." And 8 Batz occurs 7 days after the last of these days, 1 Lizard.

The day before 8 Batz and the day after

are also considered part of the ceremony. So these are the

permission days of the novice daykeeper, consisting of two different

types of shrine ritual, and the two interlap. To complicate the

matter, the second and third levels of calendar-priests, serving

lineage and canton, observe a series of shrine rituals alongside

this framework. Some of the days are shared by both tiers, while

some are observed by only the novice daykeepers and others are

observed by only the lineage and canton keepers.

The initiation rites into this highest level of calendar practice take place right after 8 Batz, on the sacred tzolkin days 9 Road, 10 Staff, and 11 Jaguar. The following chart sums up this multi-leveled initiation which culminates on the 8 Batz festival: Chart showing multi-leveled daykeeper service days, culminating in the famous 8 Monkey festival:

This inclusive system, forming the infrastructure of local government, is a highly sophisticated form of social organization. It serves the religious as well as the civil needs of the local people, and is termed a "civil-religious hierarchy." And it should be remembered that this hierarchy is not one of mutual exclusion (the type we in the West may be most familiar with), but of mutual understanding supported by an interwoven and shared worship, many times even at the same outdoor earth shrine.

So this practice really gives us a

picture of the progressive and complex social systems of the Quiché

Maya, which honor the many different levels of reality. Furthermore,

it is inherent in the Quiché world-view that these different facets

of life are not seen as irreconcilable, but as sharing the same

space, as adaptable and flexible symbols which, if altered, do not

threaten the underlying foundation of worship.

Again, this separate service runs concurrent with the other shrine visits just discussed. During the 7 Wind year, it takes place between July 21st (9 Deer) and October 11th (13 Rain), and between November 2nd (9 Monkey) and January 23rd 1994 (13 Staff). Barbara Tedlock points out that 82 days equals 3 sidereal lunar months of 27.3 days each.

This has to do with the position of the moon against the background of stars, and is apparently used by the Quiché daykeepers to adjust their trackings for slight discrepancies. On the first day of their 82-day service, they climb to the top of the sacred mountain Nima Sabal. During the night they may, as an example, observe a 4-day old moon just to the left of the Pleiades.

They return in intervals of 13 or 4 days

and finally, after 3 sidereal lunar cycles (82 days) the moon will

again be near the Pleiades. Since the phase-cycle month (the synodic

month) is slightly longer than the sidereal month, the phase will be

slightly different. Needless to say, the ancient Maya penchant for

stargazing is still alive among their descendants in Guatemala.

In the "service day" table given above, we can see that three services are observed on 8 Deer; 8 Deer occurs 7 days after 1 Ahau and 13 days after 1 Deer, the ancient Calendar Round beginning date.

Also, the year bearer in 1994 is 8 Deer - it will be interesting to observe how the traditional 8 Deer festival is coordinated with 8 Deer as the year bearer. Three Deer was the name of a famous Cakchiquel Lord, who was killed during the conquest.

This combination of dot, bar and glyph is how tzolkin dates are recorded in the archeological inscriptions one finds among the many ruins of Guatemala. The concept is simple: a bar equals 5 and a dot equals one. For example, 7, 11, and 2 are written:

A list is provided here to compare Quiché month names with the better known Yucatec Maya month names:

The Gregorian calendar is given a secondary place in these calendars for a reason. In a sense, the Mayan haab and the Gregorian year serve the same purpose. They both refer to the civil or secular count of days - the obvious yearly cycle of the earth around the sun.

The Maya preserved a 365-day approximation of the year, even after they realized a more accurate method for tracking the true solar year. They did an amazing thing by combining the haab count with a sacred count, the tzolkin, which symbolizes the mysterious inner dimension of reality. In this way, the two aspects of human experience, the sacred and the secular, the inner realm and the outer realm, are synthesized into one comprehensive cosmo-conception.

The world view which thus follows is a complete acknowledgement of spirit in matter; one in which the processes of the microcosm and macrocosm mirror each other. By comparison, the Gregorian system, though mathematically more accurate, provides only a lifeless cosmos of clockwork drudgery, an endless ticking of the minutes, hours and days.

The Maya recognized that our sense of

time defines the depth of experience of a culture, and then

endeavored to model the fantastic nature of the multidimensional

cosmos that they perceived around them. If the tzolkin/haab becomes

our primary time reference, only secondarily related to the

Gregorian system (as a convenience), we may begin to embrace a more

complete and mature attitude towards life on earth.

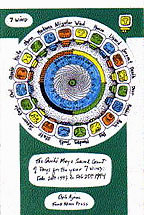

Uinal Wheels designed for the 7 Wind book. The Uinal Wheels used in the 1993 "7 Wind" calendar are now, of course, out of date.

Thus, the sacred/secular framework of the tzolkin and haab serve to mythologically and mathematically structure the observed cycle of Venus. And we've already discussed the relationship of the 260-day cycle to human gestation, as well as to the growing period of corn. In addition to this, Venus's visibility as morningstar approximately equals 260 days. We have here a Venus-corn-gestation partnership - a thread which ties together three different levels.

Now here's the clincher - In the Quiché

Popol Vuh, humans are said to be made out of corn dough! On a tree

of life carving at Palenque, corn stalks bloom with human faces. One

can see both sacred and secular concerns addressed in these ideas -

united via the tzolkin. This multi-tiered interweaving mythology

never fails to arose ones curiosity and admiration - the Maya were

surely adept visionaries and myth-makers.

Fractal harmonics is removed from the realm of abstract theory and is recognized as an inherent ordering principle of the cosmos. In essence, many of the sacred Mayan numbers and ratios, as well as Mayan philosophy, point to the Golden Proportion as one source of the Sacred Calendar's incredible properties.

The Golden Proportion is a unique ratio, explored by the ancient Greeks, and is the mathematical source for the spirals which manifest in seashells, pine cones, and other natural phenomena. It was known as PHI ( = 1.618), and was thought to represent the essential principles of fractal growth and harmonic resonance. Incredibly, the ratios 8/5 and 20/13 both approximate the Golden Proportion; PHI plays a key role in the numerical and philosophical dynamics of the tzolkin!

As the mathematical center of the Sacred Calendar, it informs all levels of the Calendar's meanings - from human gestation up to planetary cycles. For more information on this, I would refer the interested reader to my recent book Tzolkin: Visionary Perspectives and Calendar Studies, available from Four Ahau Press.

Hunab K'u

Ahau is pronounced "Ah-how." Hun is the Mayan word for one. Hunahpu is one of the hero twins in the Popol Vuh, who at the end of the story becomes the sun. The meanings of the day-sign Ahau are many: Lord, Sun, Flower, Marksman or Blowgunner. Hunab K'u, ultimately derived from One Ahau, is the highest Mayan God. As source and creatrix, this god/goddess above dualities is said to be "The One Giver of Movement and Measure."

As far as beginnings go, Hunab K'u

refers to a larger perspective than One Ahau, perhaps even to the

Galactic Center - our cosmic origins. But even One Ahau, as the

"launching off point" for tzolkin, haab and Venus, retains a similar

function as "giver of movement and measure."

And we should remember that in keeping with what we know about Mayan time, this duality is one of mutual involvement and complimentarity, not irreconcilable opposition. Furthermore, a principle of unfolding or flowering is inherent in time; movement and measure beget expansion. The cosmic conflict of yin and yang thus engender the natural processes of change and growth which surround us, and of which we are a part.

And this is a critical quality of spiral time: growth. For all of its seeming abstractness, Mayan cosmology is extremely organic. In fact, Mayan philosophy may be likened to the spiral unfolding that we see in seashells, pine cones and flowers - analogies drawn from nature. And Mayan earth worship - prayers to Tiox and Mundo - acknowledge this profound principle; that the earth is a living being, struggling through eons to bring forth the exquisite flower of spiritual awareness.

So without further tracing the journey

by which I say what I say, let me try to state things simply: The

Sacred Calendar is a cosmological model which unites inner and outer

reality and explains the earth's inherent goal of physical and

spiritual unfolding.

And what does Hunab K'u have to do with

all this? Well, everything. How can I restate this progressive and

ancient understanding of the cosmos which is embedded in the Sacred

Calendar...

In other words, the cycles of humanity are linked with the cycles of the planets - not in the cause-and-effect sense - but by virtue of a more mysterious principle of correspondence. The relationship is of a type of mirroring, an unconnected and distant affinity because both realms are unfolding with the same rhythm!

How? Because mind and world, spirit and

matter, the objective and subjective realms, are spun off from the

same moment of creation. Call it Galactic Center, the Big Bang, God

- whatever. In Mayan terms, this source is none other than Hunab K'u

- Giver of Movement and Measure.

The Maya enjoy a world-view free from the entrapments of dualistic thinking. And while this may sound hyperbolic or grandiose, we have only to look carefully at the shrouded traditions and ceremonies of the present day Quiché Maya. Still tenuously holding onto ageless traditions amidst continuous onslaughts from the outside "civilized" world, they may very well hold the secrets of a more mature perspective - one which may transform the world. How can we learn to perceive time and experience life in this seemingly more evolved way? Can we?

I feel that we can, and learning to track the tzolkin/haab calendar is a start - a doorway to that realm beyond dualities - where humanity meets and participates with the Great Spirit . . .

|

given below the day-sign

glyph by way of the "dot and bar" system of the ancient Maya.

given below the day-sign

glyph by way of the "dot and bar" system of the ancient Maya.