|

You quickly glance around the arena. You notice that everyone is aware that

the perfect time has come for the ceremony. As the Mayan king makes his way

to the top of the staircase, the sun begins to set. The sun, the ruler of

the cosmos, plays a big part in your calendar, which, in turn, demands

respect and sacrifice.

As the king stands at the top of the main pyramid of Zempoala, an eclipse begins to take place. The three perfectly placed stone rings below help him keep track of this astronomical cycle. It is also the end of a katun of the Long Count calendar, which points every fifth year to a public ceremony. As the eclipse creates one complete moment of darkness the crowd begins to chant, and the king begins this sacred meeting.

Early Thought About the Maya

It was often thought, because of the profound consistency of recorded dates,

that the Mayan's basis of religious worship was time. It is true that most

Classic inscriptions deal with dating, however, time was not necessarily an

obsession. A typical Mayan document consisted of a series of historical

backgrounds, each followed immediately by a date or astronomical expression.

In the book, The Blood of Kings, Linda Schele and Mary Ellen Miller address

this very topic. "The prominence of calendric material in Maya inscriptions

was initially taken as evidence of an obsessive fascination with time itself,

but this is no longer true."

Ernst Forstemann, a Royal Librarian of the Electorate of Saxony, also added onto Rafinesque's discovery. He identified the third digit which was a stylized shell that stood for "zero." These numbers were arranged vertically with the lowest values on the bottom. This was a big help in deciphering positional numeration and organization.

Eric Thompson's contributions, although sometimes over-analyzed, have helped

with new discoveries. Besides the fact that he completely overdid the

cosmological aspects of this culture, he pinpointed another cycle in the

ancient calendar. This measured 819 days, which he discovered was the

product of the magic numbers seven (number of the earth), nine (the heavens),

and thirteen (the underworld). This is another reason why some claimed that

the Mayan's worshiped time. The question still remains as to what this cycle

was used for. There is evidence that the cycle was important among the elite

for ceremonies associated with world directions, colors, and with the patron

gods.

The calendar combined many different counts. Each had an independent cycle

running without reference to another cycle.

The Maya recognized the same things that we do, but because their number system was vigesimal, that is, base twenty rather than base ten, their marks fall at different points in a sequence of time. A base-twenty system simply means that the Maya would count in groups of twenty rather than counting in groups of ten (as we do). Their way of writing numbers was also different.

The most common cycles found on monuments or in text are the Long Count, the

Calendar Round (Tzolk'in and Haab), the

Lord of the Night, and the Age of

the Moon. They are also associated with the Initial

and Lunar Series.

A typical Mayan date looks like this:

The smallest Long Count unit was the day, or

kin. The second was composed of

twenty kins, which equaled one uinal.

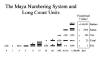

Long Count dates are expressed in place-notation system. However, in this situation, the glyph for each portion on the calendar (kin, uinal, tun, katun, and baktun) follows the number. These are usually recorded with the dots, bars, and shells. They may also have characterized portions in both head and full-figure forms. The representations of these glyphs are often called "gods" because they appear in mythological scenes that decorate pottery, (Schele, 318). Refer to figure #1. Along the left side are the dots, bars, and shells. Along the right are the representations of the kins, uinals, tuns, katuns, and baktuns.

Long Count dates are given on a day to day count, which

began in 3114 B.C.

and will end (according to Maya calendar dates) in 2012 A.D. There is still

some remaining scholarly debate on this date, yet most place the last date

for the Long Count near the end of the fourth millennium B.C.

The TZOLK'IN, or the Sacred Round, and the HAAB, or the Vague Year

Since the days are arbitrary, we will use the first twenty letters of the English alphabet (A through T), combined with Arabic numerals (1 to 13) to see how the system works. The first day would be 1A; the second, 2B; the thirteenth, 13M - but on the fourteenth day the arabic number cycles back to 1, giving the day name 1N. The next would be 2O, then 3P, etc. The twentieth day will be 7T; the twenty-first 8A; and the 260th, 13T. Two hundred and sixty days are required for the combination of 1 and A to recur.

The second calendar section is known as the Haab, or the Vague Year. This is the civil calendar of the Maya. This, because it is,

To bring the count of the full 365 days, they added a 5-day period called Wayeb "resting days" at the end of the year. It took 52 years, or a Calendar Round for the same combination of days in the Tzolk'in and Haab to continue.

The Tzolk'in and Haab are independent of each other, but they also run

simultaneously, so that any whole day has a different name in each cycle.

These two kinds of names are combined into a longer designation, such as 4 Ahau 8 Cumka -

While the Classic Maya were aware that the tropical year was actually 365.25 days, they did not use a leap year correction. This was because the connection with the Almanac year cycled back to its original start every 52 solar years.

Therefore, the dates on the Calendar Round are fixed with a never-ending cycle of 52 years. During the Haab, however, the five day resting period (the Wayeb) made up the difference for the leap year.

Lords of the Night

Since the combination of the Lords of the Night and the Calendar Round date will not repeat for 467 years, it was used to locate far more precise moments in time than is possible using the Calendar Round date. This cycle, like the rest of them, runs simultaneously with all the others. There is still some question because the names of the Mayan gods on glyph G cannot be read yet, but this was an important part of specific dating for the Maya.

To record this history, the first apparent area of purpose was found through the use of astrology and astronomy. The calculation of eclipse periods, lunar calendars, stars, and planets, played a very important role in the Maya calendar. For example, the Mayan's believed that Venus was an exceptionally malicious heavenly body.

Considering this contradiction of terms "malicious heavenly body," it is also interesting to note, that the Venus deities were shown hurling weapons and making them themselves unpleasant. The cycle of Venus was also expressed with the use of numbers - by a ring of numbers equaling 584 days. The 584 days relates to the orbit of Venus. Notice that the count for Venus was also in a circle - as a ring.

Another main display of the Maya detail of the use of these calendar systems is through their architecture. Most, if not all, of the Maya buildings were built according to the direction of the sun, on specific dates. For example, there are three stone rings of Zempoala near the main pyramid. The three rings are surmounted by 13, 28, and 40 step-like pillars, respectively. It appears that the stone monuments were used by the Totanac priests as counting devices to keep track of eclipse cycles.

There is also amazing accuracy while overlooking Tikal. Between Temple I, II, III, IV, and V, they all have a unique purpose in location. Temple II serves not only as an architectural counterweight to Temple I, but also as a horizon marker for the enigmatic "eight degrees west of north" orientation viewed from Temple V. Temple III defines the equinoctial sunset positions as seen from Temple I, while being the highest of the skyscraper pyramids. Temple IV fixes the sunset position on August 13 as seen from Temple I, (Malmstrom, 169).

Another significant monument at Tikal is known as Stela 29, exhibited as the earliest known and well-known inscriptions in the Maya lowlands with a Long Count date of 292 A.D. For archaeologists, Stela 29 is an approximate marker for the beginning of the Mayan Classic period, an era during which the Long Count was used on countless Maya inscriptions, (Price, 318).

Perhaps one of the most famous monuments is the Temple at Chichen Itza. This has been recognized as an astronomical observatory whose foundations are Mayan and whose adornments are Toltec. Perhaps the most significant alignments of this structure are those of its front door and its principal window, located just above it, both of which look out at the western horizon toward the sunset position on August 13, (Malmstrom, 157).

Most of the dates

on monumental inscriptions are associated with events in the lives of kings

who built the monuments. Still, it is not unusual to find that some of those

dates are marked with astronomical references.

The Maya would probably have considered many questions while deciding on planting and harvesting goals. For example,

With many of these questions to consider, the

Maya maintained, through precise use of their calendar, a very efficient

planting and harvesting season, which was also always correlated with

celestial worship. Even seen today, in modern Maya communities, the

Sun is

still a ruler of the cosmos for these people. It's annual passages were, and

still are, used to fix dates in the agricultural calendar.

The Maya believed that significant

moments in time had links with divinities and astrologically based

prophecies, and these associations were known, and should be recorded. Time

was not just a specific moment in existence when one needed to be at a

meeting, or meet a friend. Time became a life or death situation for the

Maya - especially during their sacrificial games and bloodletting ceremonies.

Genealogies were also very important to the Maya. For example, the

sarcophagus text found in Pacal's tomb in Palenque was inscribed with many

dates, such as births, deaths, family lines, etc. These documents represent

how important it was for the Maya to keep records (and also maintain a

positive relationship with the gods).

The Maya invented a calendar of remarkable accuracy. Indeed, they

were divine bearers of time. As progress continues to go forward, the closer

we come to find the Mayan people in time. Where in time? That answer, lies

beneath all of the knowledge the Mayan created in their calendar, so that

one day, we might find them there.

|