|

by

Michael S. Heiser

author of The Fašade

Ph.D. candidate, Hebrew and Ancient Semitic Languages,

University of Wisconsin-Madison

from

FacadeNovel Website

recovered through

WayBackMachine Website

The work of Zecharia Sitchin was brought

to my attention just over a year ago, shortly after I completed my

book,

The Facade. As a trained scholar in ancient Semitic languages

[i] with a lifelong interest in UFOs and paranormal phenomena, I was

naturally enthused about Mr. Sitchin's studies, particularly since I

had also heard he was a Sumerian scholar. I thought I had found a

kindred spirit, perhaps even a guide to navigating the possible

intersection of my academic

disciplines with ufology, a discipline

unfairly ridiculed by the academic mainstream. Unfortunately, I was

wrong. disciplines with ufology, a discipline

unfairly ridiculed by the academic mainstream. Unfortunately, I was

wrong.

What follows will no doubt trouble some readers. I have come to

learn that Mr. Sitchin has an avid following, and so that is

inevitable. Nevertheless, I feel it my responsibility as someone who

has earned credentials in the languages, cultures, and history of

antiquity to point out the errors in Mr. Sitchin's work. Indeed,

this is the academic enterprise. I have yet to find anyone with

credentials or demonstrable lay-expertise in Sumerian, Akkadian, or

any of the other ancient Semitic languages who positively assesses

Mr. Sitchin's academic work. [ii]

The reader must realize that the substance of my disagreement is not

due to "translation philosophy," as though Mr. Sitchin and I merely

disagree over possible translations of certain words. What is at

stake is the integrity of the cuneiform tablets themselves, for the

ancient Mesopotamians compiled their own dictionaries, and the words

Mr. Sitchin tells us refer to rocket ships have no such meaning

according to the ancient Mesopotamians themselves. To persist in

embracing Mr. Sitchin's views on this matter (and a host of others)

amounts to rejecting the legacy of the ancient Sumerian and Akkadian

scribes whose labors have come down to us from the ages.

Put simply, is it more coherent to

believe a Mesopotamian scribe's definition of a word, or Mr.

Sitchin's.

Lexical Lists:

An Introduction to Sumero-Akkadian Dictionaries

[iii]

Lists of words are a common feature among the thousands of Sumerian

and Akkadian cuneiform tablets which have been discovered by

archaeologists. Many are just groupings of common words, while

others represent an inventory of the word meanings of the languages

used in Mesopotamia. These are the lists of importance for our

purposes. These "lexical lists," as scholars call them, appear among

the earliest cuneiform tablets, at the beginning of the third

millennium B.C.

These lists were indispensable to the

19th century scholars who deciphered the Sumerian and Akkadian

texts, for they were used to compile modern dictionaries of these

languages. Today all major lexical texts have been published in the

multi-volume set, Materials for the Sumerian Lexicon, [iv] begun by

Benno Landsberger in the 1930s. The modern Sumerian Dictionary

Project still underway at my alma mater, the University of

Pennsylvania, utilizes these lists.

The two standard modern dictionaries,

W. von Soden's Akkadisches Handworterbuch (3 volumes) and

the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, also utilize these materials. It is

indeed a rare instance where ancient dictionaries of a dead language

form the core of the modern dictionaries used by scholars of today.

Such is the case for the ancient languages of Sumer and Akkad.

Sadly, Mr. Sitchin neglects these resources.

The typical arrangement of the scribes on the multi-lingual lexical

tablets was to place the Sumerian pictogram on the left hand side.

Going from left to right, the next column often had the name of the

Sumerian pictogram used by scribes, followed by the Akkadian

translation. At times another column followed, giving the

translation in other ancient languages, such as cuneiform Hittite.

In this way, the Mesopotamians themselves created bilingual or

multi-lingual dictionaries for the languages of the people of

Mesopotamia - and for us, if we care to use them!

First

Things: The Meaning of Sumerian "MU"

On pages 140-143 of

The 12th Planet, we read that Mr. Sitchin

defines the Sumerian MU as "an oval-topped, conical object,"

[v] and "that which rises straight." [vi] Mr. Sitchin cites no

Sumerian dictionary for these meanings. A check of the dictionaries

contained in Sumerian grammars and the online Sumerian dictionary

reveal no such word meanings. [vii] But why trust modern scholars

when we can check with the Mesopotamian scribes themselves.

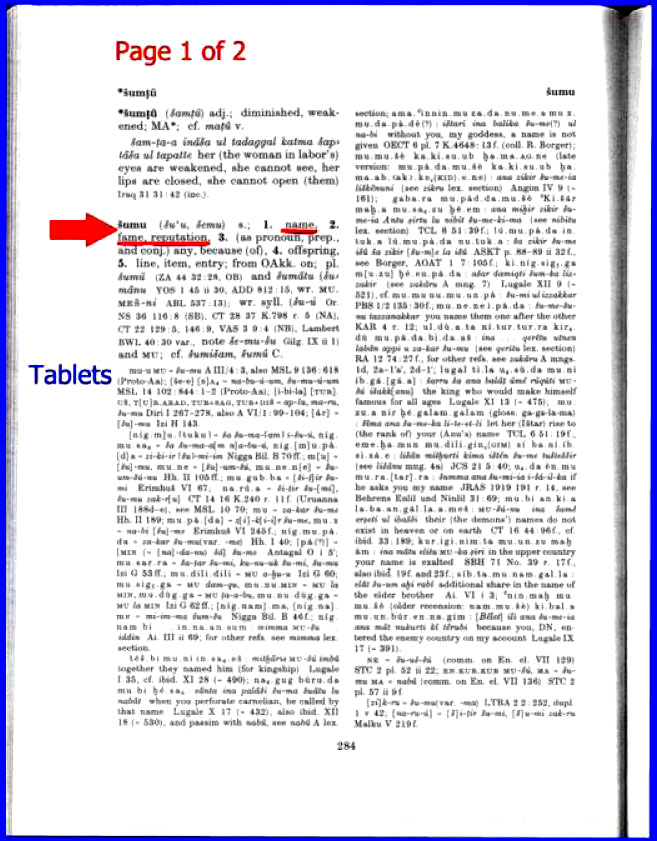

In his technical but stimulating study of Sumerian and Mesopotamian

terminology for the cosmos, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography,

Mesopotamian scholar W. Horowitz lays out the meaning of the

Sumerian word "MU" directly as the Mesopotamian lexical lists have

it. What follows below is his layout. In discussing the meaning of

the Akkadian word "shamu," in his book, Horowitz gathered all the

lexical list data for that word. [viii] Note that the word "MU" in

the left-hand (Sumerian) was among the cuneiform dictionary entries

for "shamu."

A discussion of the meanings follows the

entries. Briefly, "shamu" in Akkadian here means "heaven" (or part

of the sky/heavens) or perhaps "rain." [ix] According to the scribal

tablets themselves, the meaning is not "that which rises straight,"

or "conical object" (i.e., "rocket ship"). This is the verdict of

the scribes themselves, not this writer.

The red explanatory insertions are my

own:

Mr. Sitchin goes on to claim (p. 143)

that the Sumerian syllable MU was adopted into Semitic languages as

"SHU-MU," which he translates as "that which is a MU" (by

implication, "that which is a rocket ship"). Allegedly, "SHU-MU"

then morphed into Akkadian shamu and Biblical Hebrew shem.

We will consider the Akkadian word

first, and then the Hebrew word.

The Meaning of

Akkadian "shamu"

Does Akkadian shamu come from Sitchin"s "SHU-MU". Does

Sumerian even have a word that means "that which is a MU". Contrary

to Mr. Sitchin, Akkadian shamu does NOT derive from SHU-MU,

nor does shamu mean "that which is a MU."

First, Mr. Sitchin's translation of shu-mu presupposes that "SHU-"

is what's called in grammar a "relative pronoun" (the classification

of pronouns in all languages that mean: "that which"). Mr. Sitchin

is apparently unaware of Sumerian grammar at this point, because the

Sumerian language does not have a class of pronouns that are

relative pronouns! One need only consult a Sumerian grammar to find

this out, such as John L. Hayes, A Manual of Sumerian

Grammar (p.88).

Second, in light of the fact that there is no "SHU-MU" form in

Sumerian (since Sitchin's relative pronoun "SHU-" is concocted), it

logically follows that Akkadian shamu did not derive from a

Sumerian "SHU-MU." Nevertheless, Akkadian does have a word shumu,

but it does not come from Sumerian "SHU-MU" (since that combination

never existed in light of Sumerian grammar's lack of the assumed

relative pronoun). In fact, the shumu of Akkadian undermines

Sitchin's entire argument when it comes to the Tower of Babel

account (see below for more on Akkadian shumu).

Returning to shamu, the Akkadian word shamu can have multiple

meanings, depending on its original root origin. The lexical lists

above presuppose a shamu that comes from the Akkadian word

shama'u or shamamu, both of which mean "heaven," as in a

place or portion of the sky. Notice how similar shamu is to both

shama'u and shamamu. Only the extra letter marks them as different,

marked either by an apostrophe (shama'u) in English [x] or an "m" (shamamu).

It turns out that our word shamu

in the lexical lists above is a contraction of either shama'u

or shamamu (the word loses a letter just like in English

"didn't" for "did not").

The Meaning of

Biblical Hebrew "shem"

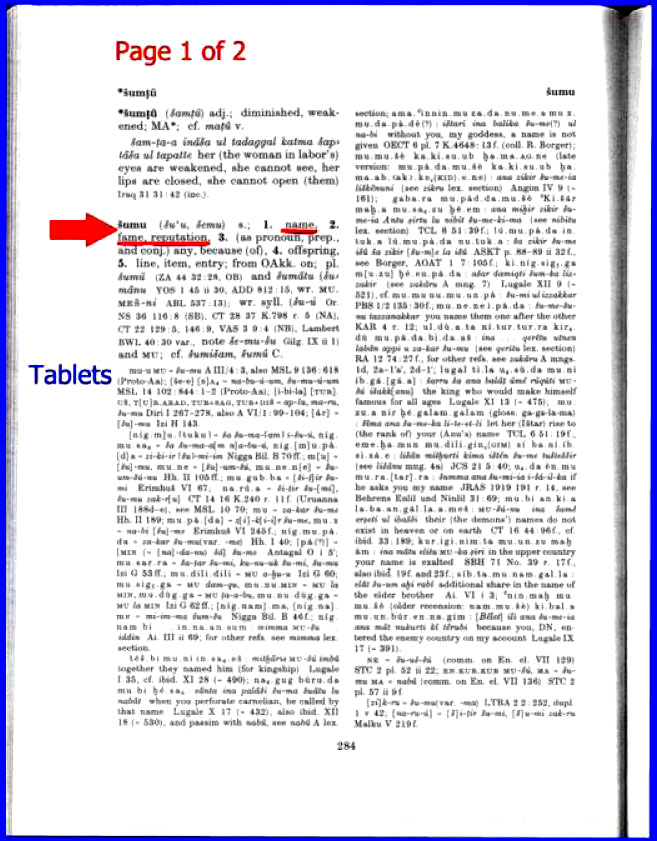

As noted above, there is an Akkadian word shumu. This word has its

own meaning, a meaning that did in fact get absorbed into Biblical

Hebrew, from whence Hebrew shem originated. Both this

Akkadian shumu and Hebrew shem mean "name" or "renown," the

word meanings Mr. Sitchin ridicules in The 12th Planet on his way to

fabricating rocket ships in Mesopotamia and the Biblical Tower of

Babel story.

Other than the concocted word origin (SHU.MU),

how do we know that Mr. Sitchin's word meanings are wrong. Here are

the entries in the gold standard Akkadian dictionary, The Chicago

Assyrian Dictionary painstakingly produced over several decades by

scholars of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Note that the entries have specific references in which tablets (and

hence contexts) this word shamu occurs. [xi] The word

meanings are right from the tablets themselves.

Unlike Mr. Sitchin's work, which cites

no dictionary entries for his meanings:

A Word on the Tower

of Babel Accounts in both Sumerian and Biblical Literature "

The Common Sense of

Context

In the absence of any linguistic support for his rocket ships, Mr.

Sitchin's supporters might claim a linguistic cover-up. No, scholars

aren't hiding "rocket ship" meanings in the cuneiform tablets. In

fact, the discerning reader of the Sumerian and biblical Babel

accounts need not retreat to linguistics at all to know Mr.

Sitchin's theories are nonsensical.

Consider first the biblical story of

Genesis 11:1-9:

1 And the whole earth was of one

language, and of one speech.

2 And it came to pass, as they

journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of

Babylon; and they dwelt there.

3 And they said one to another, Go

to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had

brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar.

4 And they said, Go to, let us build

us a city and a tower, whose top [may reach] unto heaven; and

let us make us a name (shem) lest we be scattered abroad upon

the face of the whole earth.

5 And the Lord came down to see the

city and the tower, which the children of men built.

6 And the Lord said, Behold, the

people are one, and they have all one language; and this they

begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which

they have imagined to do.

7 Let us go; let us go down, and

there confound their language, that they may not understand one

another's speech.

8 So the Lord scattered them abroad

from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they stopped

building the city.

9 Therefore is the name of it called

Babel; because the Lord confounded the language of all the earth

there: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the

face of all the earth.

The point here is brief. Note two

obvious facts from the plain English:

(1) The people are not building the

shem; they are building "a city and a tower" (verse 4).

The Hebrew words here are not shem in either case, they are

ir ("city"; pronounced ghir) and migdal ("tower").

The word shem comes later in the verse, and is the

purpose for building the city and tower to make a great name for

themselves, just what the Akkadian word shumu means!

(2) The tower is being built with brick and mortar (verse 3) "

what rocket ships are made of bricks and mortar"

Again, Mr. Sitchin"s supporters could

claim some sort of Christian or Jewish conspiracy to obscure the

construction of a rocket ship. If so, then the Sumerians themselves

started the cover-up (leaving only Mr. Sitchin correct).

Here's their version, from

Enuma Elish

(Tablet VI: lines 59-64):

The Anunnaki set to with hoes

(Unusual tools for rocket-building!)

One full year they made its bricks

(A rocket made of bricks! Sounds like Genesis 11.)

They raised up Esagila, the counterpart to Apsu,

They built the high ziggurat of counterpart Apsu

(A ziggurat, not a shem or shumu)

For Anu-Enlil-Ea they founded his dwelling.

The point here is that in the very story

Mr. Sitchin uses to create a parallel between Sumer and the

Old

Testament, the Anunnaki are clearly constructing a tower made of

bricks - not a spaceship. No, Virginia, there were no rocket ships

in Mesopotamia.

References

[i] I hold two masters degrees, one

in Ancient History from the University of Pennsylvania (my

fields were Egyptology and Syria-Palestine), and another from

the University of Wisconsin-Madison in Hebrew and Semitic

Languages. I am currently working on my dissertation at the

latter institution in Hebrew and Semitic Languages to complete

the PhD. I am in the final stage of that task. My coursework

enables me to do translation work in roughly a dozen ancient

languages, among them Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Akkadian,

Sumerian, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Phoenician, Ugaritic, and

Moabite.

[ii] I have only read about Mr. Sitchin's credentials (as a

journalist, not an ancient linguist) from websites and book

flaps written by people with no background in the ancient

languages. Thus far, I have been unable to find proof that Mr.

Sitchin knows any of the languages he references in his books -

and his books provide little that would convince me he does.

[iii] Much of what follows in this section is drawn from the

excellent article "Ancient Sumerian Lexicography," by University

of Chicago Sumerian professor (emeritus) Miguel Civil (in

Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, 4 vols., ed. Jack M. Sasson, 1995).

[iv] Entries are in German.

[v] Page 140. Mr. Sitchin acknowledges that the object on the

Byblos coin is not described with the word "MU" on the coin (the

writing is Greek, and the written language of Byblos was Byblian-Phoenician),

but due to the object's shape combined with Mr. Sitchin's

contrived word meaning, the object "can only be a mu" (p. 140).

[vi] Page 141. According to Mr. Sitchin, this is the syllable's

"primary meaning." No dictionary or tablet / lexical list

information is supplied by Mr. Sitchin for this claim.

[vii] For example: M.L. Thomsen, The Sumerian Language: An

Introduction to Its History and Grammatical Structure

(Copenhagen 1984); J.L. Hayes, A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and

Texts: Second Revised and Expanded Edition (Malibu, 2000);

A. Deimel, Sumerisches Lexikon (Rome 1947).

[viii] The extant lexical lists available are labeled by

scholars as K.2035 (column ii 17-33) and "2R50." The "MSL number

in the right hand column is the number of the list as it is

reproduced in Landsberger's Materials for the Sumerian Lexicon.

Interestingly, the Sumerian "ME" (described by Sitchin as a

space suit) is also equated with shamu, and thus shares the

meanings noted above.

[ix] The meaning of shamu in Akkadian depends on its AKKADIAN

root origin (not a contrived Sumerian heritage); see the

discussion.

[x] English doesn't have the sound represented by this Semitic

letter, the aleph - a stop in the back of the throat.

[xi] Due to the problem of file size caused by the images, I

have selected only two pages of what is actually a multi-page

entry. The reader is directed to the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary

for the full discussion.

|