|

Nueva York, 05 de

septiembre de 2001.

Gracias a un nuevo y potente telescopio de rayos X, se ha encontrado

evidencia casi irrefutable de la existencia de un descomunal agujero

negro en el centro de nuestra galaxia, según un grupo de astrónomos.

Los científicos coinciden generalmente en que casi todas las

galaxias giran en torno a un agujero negro. Ya se había calculado

que el centro de nuestra galaxia, la Vía Láctea, contenía algo muy

denso y masivo, y la mayoría de los expertos creía que se trataba de

un agujero negro.

|

Los hoyos negros son

cuerpos celestes extremadamente densos. Su gravedad es tan poderosa

que ni siquiera la luz puede escapar de ella, por lo que son

invisibles para los telescopios convencionales.

Para estudiarlos,

los astrónomos observan las estrellas y gases que se arremolinan

alrededor del centro de un hoyo negro, antes de caer en su núcleo

invisible como agua por desagüe. Antes de caer allí, la materia se

amontona como troncos estancados en un río. Allí se calienta y

genera rayos X.

|

|

En el nuevo estudio,

dirigido por Frederick Baganoff del

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT, los científicos usaron

el telescopio de rayos X Chandra de la NASA,

para observar el brillo de los rayos X producido donde suponen que

se encuentra el borde del hoyo negro. La clara imagen de tal brillo

recién obtenida por los científicos es la primera en su tipo.

|

|

El brillo aumentó y menguó

durante un periodo de 10 minutos, el tiempo que tomó a la luz el

viaje por unos 150 millones de kilómetros, alrededor del borde del

hoyo negro. Eso significa que el objeto, presuntamente un hoyo

negro, es bastante pequeño si se consideran las dimensiones de otros

objetos en el espacio. La masa que contiene dentro de su área es

unos 2.6 millones de veces mayor a la del sol. El supuesto hoyo

negro está situado a unos 24 mil años luz de la Tierra.

Los científicos también

detectaron enormes lóbulos de gas supercaliente, que en la

fotografía aparecen como burbujas rojas. Es probable que los lóbulos

sean restos de enormes explosiones ocurridas cerca del agujero negro

en los últimos 10.000 años. |

|

Los agujeros negros son

monstruosos succionadores de materia en el espacio, que atraen

cualquier cosa de manera tan fuerte que nada, incluso la luz, puede

escapar de la succión. Por esa razón, nadie ha visto jamás un

agujero negro, pero los astrónomos saben de su existencia al

observar lo que sucede a su alrededor.

Richard Mushotzky, astrónomo del Centro Goddard de Vuelos

Espaciales de la NASA, en Greenbelt, Maryland, dijo que los

nuevos descubrimientos impulsan las evidencias previas sobre la

existencia de un hoyo negro en el centro de la Vía Láctea. El

estudio será publicado en la edición del jueves de la revista

Nature.

El poderoso telescopio

Chandra, que utiliza cuatro espejos cilíndricos, fue lanzado a

órbita hace dos años. Los rayos X son absorbidos por la atmósfera y

no pueden ser detectados por telescopios en la Tierra. Los

científicos creen que existen miles de millones de hoyos negros en

el universo, incluidos muchos que son miles de veces más masivos y

luminosos que el objeto detectado en el centro de la Vía Láctea. |

|

NASA-GSFC NEWS

RELEASE

Posted: September 18, 2000

|

An illustration of a supermassive black hole

at the center of a galaxy.

Photo: NASA

Scientists have

designed and successfully tested a new type of X-ray telescope

that, when fully developed and placed in orbit, may capture the

first images of a black hole and resolve details of nearby stars

as clearly as we see our own Sun today. The report is published

in the September 14 issue of Nature.

The X-ray telescope

designed by University of Colorado and NASA has the potential of

providing resolution a thousand times sharper than the finest

images available today in any wavelength and a million times

better than what current X-ray telescopes can muster. In orbit,

such an instrument could resolve a region the size of a dinner

plate on the surface of the Sun. The telescope employs a

technique called interferometry, a process of coupling two or

more telescopes together to synthetically build an aperture

equal to the separation of the telescopes. |

|

"Through the power of ultra-high resolution, we could journey to

distant places without need for a warp drive," said Dr. Webster

Cash, a professor at University of Colorado and lead author on the

Nature article. "This new approach allows X-ray astronomers to

essentially jump from telescopes with resolution no finer than what

an amateur uses in the backyard to an observatory far more precise

than Hubble."

|

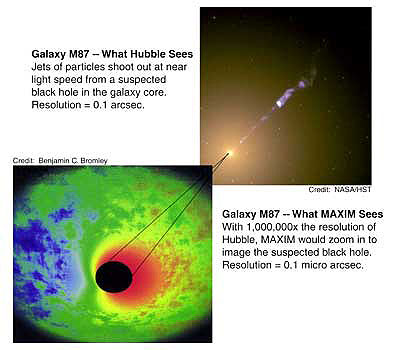

Comparing

Hubble data design concept for the MAXIM Pathfinder.

Photo: NASA

X-ray telescopes are

essential for studying black holes up close, said Dr. Cash,

because the X-ray band is the dominant radiation in the region

directly surrounding these strange objects. X rays can also

travel through the dusty Milky Way galaxy in ways that optical

light cannot. X-ray telescopes must be placed in orbit, for

celestial X rays do not penetrate the Earth's atmosphere.

To see Multimedia in

"The Universe

through the Hubble"

(file 3.4 Mega / 2-3

minutes to load)

"click"

HERE |

|

Dr.

Cash and his colleagues have achieved 100 milliarcsecond

resolution (similar to Hubble) in the laboratory with their X-ray

interferometer. This is a five-fold improvement over the best

conventional X-ray telescopes, which achieve 500 milliarcsecond

resolution.

This interferometry design is currently under study at Goddard Space

Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., for two proposed NASA missions with

the ultimate goal of imaging a black hole. MAXIM, the Microarcsecond

X-ray Imaging Mission, could achieve 100-nanoarcsecond resolution

and would entail a fleet of spacecraft with separate optics flying

in precise formation. The MAXIM Pathfinder would be a smaller

mission with all the X-ray optics on one spacecraft, achieving

100-microarcsecond resolution. These interferometers would

complement, not replace, large area X-ray telescopes also planned

for the future.

With 100 microarcsecond resolution, astronomers could image the

coronae of nearby stars, seeing the actual disks of other stars

which appear now only as points of light. With 100 nanoarcsecond

resolution, astronomers could attain one of astronomy's ultimate

goals -- imaging a black hole. (It is a thousand-fold increase in

each jump from "milli" to "micro" to "nano".)

"Black holes hold an almost mythical attraction," said

Dr. Nicholas

White, head of Goddard's Laboratory for High Energy Astrophysics.

"Compelling evidence that black holes exist has come from

observations of their gravitational effect on nearby objects, but

the ultimate proof is yet to come -- a direct image of the 'black

dot'. The X-ray interferometer may take us there."

|

Preliminary design concept for the MAXIM Pathfinder.

Photo: NASA

Interferometry is a common practice in radio astronomy (e.g. the

Very Large Baseline Array) and an emerging technique for optical

astronomers (e.g. the Keck Observatory). The technique is

similar to the way sound waves can be combined to either cancel

each other out (resulting in silence) or amplify the sound.

NASA's first orbiting optical interferometer, called the Space Interferometry Mission, is scheduled for launch in 2006.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory, NASA's most powerful X-ray

telescope to date, has generated a multitude of major

astronomical discoveries in the 15 months since its launch.

|

|

Chandra achieves its unprecedented 500 milliarcsecond resolution not

through interferometry but rather through highly polished and

carefully aligned mirrors.

Joining Dr. Cash on the Nature article are Drs. Ann Shipley and

Steve Osterman, both at University of Colorado, and Dr. Marshall Joy of

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. Testing of

the prototype X-ray interferometer took place at NASA-Marshall in

1999.

The proposed MAXIM and Pathfinder missions would launch after 2010.

|