|

from

Wikipedia Website

|

Giordano Bruno

(1548 Nola – Rome, February 17, 1600) was an Italian

philosopher, priest, cosmologist, and occultist. Bruno

is known for his system of mnemonics based upon

organized knowledge and as an early proponent of the

idea of an infinite and homogeneous universe. Burned at

the stake as a heretic by the Roman Inquisition, Bruno

is often seen as the first martyr to the cause of

free-thought. [1] |

Early life

Born in Nola (in Campania, then part of the Kingdom of Naples) in

1548, he was originally named Filippo Bruno. His father was Giovanni

Bruno, a soldier. At the age of eleven he traveled to Naples to

study the Trivium. At 15, Bruno entered the Dominican Order, taking

the name of Giordano from Giordano Crispo, his metaphysics tutor. He

continued his studies, completing his novitiate, and becoming an

ordained priest in 1572.

He was interested in philosophy, and was an expert on the art of

memory; he wrote books on mnemonic technique, which Frances Yates

contends may have been disguised Hermetic tracts. The writings

attributed to Hermes Trismegistus had played an important role in

the Renaissance Neoplatonic revival. At that time they were thought

to date uniformly to the earliest days of ancient Egypt and to

encode a form of "pristine wisdom" ("prisca philosophia").

They are

now believed to date mostly from about 300 A.D. and are associated

with Neoplatonism.

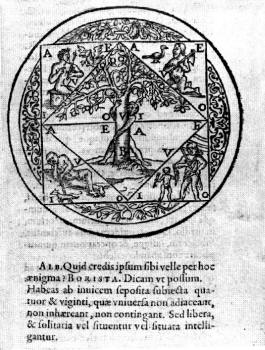

Woodcut illustration of one of Giordano Bruno's mnemonic devices:

in

the spandrels are the four classical elements: earth, air fire, water

While the Hermetic Tradition was a major influence on Bruno, he

also absorbed and developed the heliocentric ideas of Copernicus.

Other significant influences included Thomas Aquinas, whose works he

had to study in depth as a novice and for whom he always expressed a

curiously deep admiration ([2]), Averroes, whose idea of a universal

mind resonates through Bruno's work, Duns Scotus, the Renaissance

Neoplatonist Marsilio Ficino, and, last but certainly not least,

Nicholas of Cusa's ideas on infinity and indeterminacy, particularly

the idea of an infinite universe where Earth has no special place.

Bruno developed a pantheistic hylozoistic system, essentially

incompatible with orthodox Christian Trinitarian beliefs.

In 1576 he left Naples to avoid the attention of the Inquisition. He

left Rome for the same reason and abandoned the Dominican order. He

travelled to Geneva and briefly joined the Calvinists, before he was

excommunicated, ostensibly for slandering the philosophy professor

Antoine de la Faye. After Bruno apologized his excommunication was

revoked, but in autumn 1579, deeply disappointed by Calvinist

intolerance, he left for France.

He went first to Lyon, but he could not find work there and in late

1579 he arrived in Toulouse, at that time a Catholic stronghold,

where he obtained a position as lecturer of philosophy. After the

bitter experience in Geneva, he also tried to revert to mainstream

Catholicism, but he was denied absolution by the Jesuit priest that

he approached.

After religious strife broke out in

Toulouse in summer 1581, he moved to Paris, where first he held a

cycle of thirty lectures on theological topics. At this time, he

also began to gain fame for his prodigious memory. Bruno's feats of

memory were based, at least in part, on his elaborate system of

mnemonics, but some of his contemporaries found it easier to

attribute them to magical powers. His talents attracted the

benevolent attention of the king Henry III, who supported a

conciliatory, middle-of-the-road cultural policy between Catholic

and Protestant extremism.

In Paris he enjoyed the protection of his powerful French patrons.

During this period, he published several works on mnemonics, a.o.

"De umbris idearum" (The Shadows of Ideas, 1582), "Ars Memoriae"

(The Art of Memory, 1582), "Cantus Circaeus" (Circe's Song, 1582),

based on his model of organised knowledge, opposed to that of Petrus

Ramus. In 1582 Bruno also published a comedy summarizing some of his

philosophical positions, titled "Il Candelaio" ("The Torchbearer").

Travel years

In April 1583, he went to England with letters of recommendation

from Henry III, working for the French ambassador, Michel de

Castelnau. There he became acquainted with the poet Philip Sidney

and with the Hermetic circle around John Dee. He also unsuccessfully

sought a teaching position at Oxford, where however he held

lectures. His views spurred controversy, notably with John

Underhill, Rector of Lincoln College and from 1589 bishop of Oxford,

and George Abbot, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury, who

poked fun at Bruno for supporting “the opinion of Copernicus that

the earth did go round, and the heavens did stand still; whereas in

truth it was his own head which rather did run round, and his brains

did not stand still.”([3]) and who reports accusations of

plagiarising Ficino's work. Still, the English period was a fruitful

one.

During that time Bruno completed and

published some of his most important works, the "Italian Dialogues",

including the cosmological tracts "La Cena de le Ceneri" (The Ash

Wednesday Supper, 1584), "De la Causa, Principio et Uno" (On Cause,

Prime Origin and the One, 1584), "De l'Infinito Universo et Mondi"

(On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, 1584) as well as "Lo Spaccio

de la Bestia Trionfante" (The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast,

1584) and "De gl' Heroici Furori" (On Heroic Frenzies, 1585).

Some of the works that Bruno published

in London, notably the "The Ash Wednesday Supper", appear to have

given offense. It was not the first time, nor was it to be the last,

that Bruno's controversial views coupled with his abrasive sarcasm

lost him the support of his friends.

In October 1585, after the French embassy in London was attacked by

a mob, he returned to Paris with Castelnau, finding a tense

political situation. Moreover, his 120 theses against Aristotelian

natural science and his pamphlets against the Roman Catholic

mathematician Fabrizio Mordente soon put him in ill favor. In 1586,

following a violent quarrel about Mordente's invention, "the

differential compass", he left France for Germany.

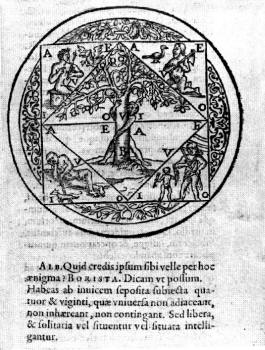

Woodcut from Articuli centum et sexaginta adversus huius tempestatis

mathematicos atque philosophos,

Prague 1588

In Germany he failed to

obtain a teaching position at Marburg, but was granted permission to

teach at Wittenberg, where he lectured on Aristotle for two years.

However, with a change of intellectual climate there, he was no

longer welcome, and went in 1588 to Prague, where he obtained 300 taler from Rudolf II, but no teaching position. He went on to serve

briefly as a professor in Helmstedt, but had to flee again when he

was excommunicated by the Lutherans, continuing the pattern of

Bruno's gaining favor from lay authorities before falling foul of

the ecclesiastics of whatever hue.

1591 found him in Frankfurt. Apparently, during the Frankfurt Book

Fair, he received an invitation to Venice from the patrician

Giovanni Mocenigo, who wished to be instructed in the art of memory,

and also heard of a vacant chair in mathematics at the University of

Padua. Apparently believing that the Inquisition might have lost

some of its impetus, he returned to Italy.

He went first to Padua, where he taught briefly, and applied

unsuccessfully for the chair of mathematics, that was assigned

instead to Galileo Galilei one year later. Bruno accepted Mocenigo's

invitation and moved to Venice in March 1592. For about two months

he functioned as an in-house tutor to Mocenigo. When Bruno announced

his plan to leave Venice to his host, the latter, who was unhappy

with the teachings he had received and had apparently developed a

personal rancour towards Bruno, denounced him to the Venetian

Inquisition, that had Bruno arrested on May 22, 1592.

Among the numerous charges of blasphemy

and heresy brought against him in Venice, based on Mocenigo's

denunciation, was his belief in the plurality of worlds, as well as

accusations of personal misconduct. Bruno defended himself

skillfully, stressing the philosophical character of some of his

positions, denying others and admitting that he had had doubts on

some matters of dogma.

The Roman Inquisition, however, asked

for his transferal to Rome. After several months and some quibbling

the Venetian authorities reluctantly consented and Bruno was sent to

Rome in February 1593.

The monument to Bruno

in the place he was executed,

Campo de' Fiori in

Rome.

Close-up of the

statue

Trial and death

In Rome he was imprisoned for seven years during his lengthy trial,

lastly in the Tower of Nona. Some important documents about the

trial are lost, but others have been preserved, among them a summary

of the proceedings that was rediscovered in 1940. [2] The numerous

charges against Bruno, based on some of his books as well as on

witness accounts, included blasphemy, immoral conduct, and heresy in

matters of dogmatic theology, and involved some of the basic

doctrines of his philosophy and cosmology.

Luigi Firpo lists them as follows: [3]

-

Holding opinions contrary to the

Catholic Faith and speaking against it and its ministers.

-

Holding erroneous opinions about

the Trinity, about Christ's divinity and Incarnation.

-

Holding erroneous opinions about

Christ.

-

Holding erroneous opinions about

Transubstantiation and Mass.

-

Claiming the existence of a

plurality of worlds and their eternity.

-

Believing in metempsychosis and

in the transmigration of the human soul into brutes.

-

Dealing in magics and

divination.

-

Denying the Virginity of

Mary.

Bruno continued his Venetian defensive

strategy, which consisted in bowing to the Church's dogmatic

teachings, while trying to preserve the basis of his philosophy. In

particular Bruno held firm to his belief in the plurality of worlds,

although he was admonished to abandon it. His trial was overseen by

the inquisitor, Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, who demanded a full

recantation, which Bruno eventually refused. Instead he appealed in

vain to Pope Clement VIII, hoping to save his life through a partial

recantation.

The Pope expressed himself in favor of a

guilty verdict. Consequently, Bruno was declared a heretic, handed

over to secular authorities on February 8, 1600. At his trial he

listened to the verdict on his knees, then stood up and said:

"Perhaps you, my judges, pronounce

this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it."

A month or so later he was brought to

the Campo de' Fiori, a central Roman market square, his tongue in a

gag, tied to a pole naked and burned at the stake, on February 17,

1600.

The conflicts over

his execution

All his works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in

1603. Four hundred years after his execution, official expression of

"profound sorrow" and acknowledgement of error at Bruno's

condemnation to death was made, during the papacy of John Paul II.

Attempts were made by a group of professors in the Catholic

Theological Faculty at Naples, led by the Nolan Domenico Sorrentino,

to obtain a full rehabilitation from the Catholic authorities.

In 1885 an international committee for a monument to Bruno on the

site of his execution was formed [4], including Victor Hugo, Herbert

Spencer, Ernest Renan, Ernst Haeckel, Henrik Ibsen and Ferdinand

Gregorovius. [5] [6] The monument was sharply opposed by the

clerical party, but was finally erected by the Rome Municipality and

inaugurated in 1889.

Some authors have characterized Bruno as a "martyr of science",

making a parallel to the Galileo affair. They assert that, even

though Bruno's theological beliefs were an important factor in his

heresy trial, his Copernicanism and cosmological beliefs also played

a significant role for the outcome. Others oppose such a fatal role

of the Copernican system for Bruno, and claim the connection to be

exaggerated, or outright false. [7] [8]

The Vatican webpage about Bruno's trial provides a different

perspective:

"In the same rooms where Giordano

Bruno was questioned, for the same important reasons of the

relationship between science and faith, at the dawning of the

new astronomy and at the decline of Aristotle’s philosophy,

sixteen years later, Cardinal Bellarmino, who then contested

Bruno’s heretical theses, summoned Galileo Galilei, who also

faced a famous inquisitorial trial, which, luckily for him,

ended with a simple abjuration." [9]

The cosmology of

Bruno's time

According to Aristotle and Plato, the universe was a finite sphere.

Its ultimate limit was the primum mobile, whose diurnal rotation was

conferred upon it by a transcendental God, not part of the universe,

a motionless prime mover and first cause. The fixed stars were part

of this celestial sphere, all at the same fixed distance from the

immobile earth at the center of the sphere. Ptolemy had numbered

these at 1,022, grouped into 48 constellations. The planets were

each fixed to a transparent sphere.

In the first half of the 15th century Nicolaus Cusanus reissued the

ideas formulated in Antiquity by Democritus and Lucretius and

dropped the Aristotelean cosmos. He envisioned an infinite universe,

whose center was everywhere and circumference nowhere, with

countless rotating stars the Earth being one of them, of equal

importance. He also considered neither the rotation orbits were

circular, nor the movement was uniform.

In the second half of the 16th century, the theories of Copernicus

began diffusing through Europe. Copernicus conserved the idea of

planets fixed to solid spheres, but considered the apparent motion

of the stars to be an illusion caused by the rotation of the Earth

on its axis; he also preserved the notion of an immobile center, but

it was the Sun rather than the Earth. Copernicus also argued the

Earth was a planet orbiting the Sun once every year. However he

maintained the Ptolemaic hypothesis that the orbits of the planets

were composed of perfect circles - deferents and epicycles - and

that the stars were fixed on a stationary outer sphere.

Few astronomers of Bruno's time accepted Copernicus's heliocentric

model. Among those who did were the Germans Michael Maestlin

(1550-1631), Cristoph Rothmann, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), the

Englishman Thomas Digges, author of A Perfit Description of the

Caelestial Orbes, and the Italian Galileo Galilei (1564-1642).

Bruno's cosmology was strongly influenced by Cusanus and Copernicus.

Bruno's cosmology

Bruno believed, as is now universally accepted, that the Earth

revolves and that the apparent diurnal rotation of the heavens is an

illusion caused by the rotation of the Earth around its axis. He

also saw no reason to believe that the stellar region was finite, or

that all stars were equidistant from a single center of the

universe.

In 1584, Bruno published two important philosophical dialogues, in

which he argued against the planetary spheres. (Two years later,

Rothmann did the same in 1586, as did Tycho Brahe in 1587.) Bruno's

infinite universe was filled with a substance -- a "pure air",

aether, or spiritus -- that offered no resistance to the heavenly

bodies which, in Bruno's view, rather than being fixed, moved under

their own impetus.

Most dramatically, he completely

abandoned the idea of a hierarchical universe. The Earth was just

one more heavenly body, as was the Sun. God had no particular

relation to one part of the infinite universe more than any other.

God, according to Bruno, was as present on Earth as in the Heavens,

an immanent God, the One subsuming in itself the multiplicity of

existence, rather than a remote heavenly deity.

Bruno also affirmed that the universe was homogeneous, made up

everywhere of the four elements (water, earth, fire, and air),

rather than having the stars be composed of a separate quintessence.

Essentially, the same physical laws would operate everywhere,

although the use of that term is anachronistic. Space and time were

both conceived as infinite. There was no room in his stable and

permanent universe for the Christian notions of divine Creation and

Last Judgement.

Under this model, the Sun was simply one more star, and the stars

all suns, each with its own planets. Bruno saw a solar system of a

sun/star with planets as the fundamental unit of the universe.

According to Bruno, infinite God necessarily created an infinite

universe, formed of an infinite number of solar systems, separated

by vast regions full of Aether, because empty space could not exist.

(Bruno did not arrive at the concept of a galaxy.) Comets were part

of a synodus ex mundis of stars, and not -- as other authors

sustained at the time -- ephemeral creations, divine instruments, or

heavenly messengers. Each comet was a world, a permanent celestial

body, formed of the four elements.

Bruno's cosmology is marked by infinitude, homogeneity, and

isotropy, with planetary systems distributed evenly throughout.

Matter follows an active animistic principle: it is intelligent and

discontinuous in structure, made up of discrete atoms. This animism

(and a corresponding disdain for mathematics as a means to

understanding) is the most dramatic respect in which Bruno's

cosmology differs from what today passes for a common-sense picture

of the universe.

During the later 16th century, and throughout the 17th century,

Bruno's ideas were held up for ridicule, debate, or inspiration.

Margaret Cavendish, for example, wrote an entire series of poems

against "atoms" and "infinite worlds" in Poems and Fancies in 1664.

His true, if partial, rehabilitation would have to wait for the

implications of Newtonian cosmology.

Bruno's overall contribution to the birth of modern science is still

controversial. Some scholars follow Frances Yates stressing the

importance of Bruno's ideas about the universe being infinite and

lacking structure as a crucial crosspoint between the old and the

new. Others disagree. Others yet see in Bruno's idea of multiple

worlds instantiating the infinite possibilities of a pristine,

indivisible One a forerunner of Everett's Many-worlds interpretation

of quantum mechanics.[10]

Quotations

"Firstly, I say that the theories on

the movement of the earth and on the immobility of the firmament

or sky are by me produced on a reasoned and sure basis, which

doesn’t undermine the authority of the Holy Scriptures […]. With

regard to the sun, I say that it doesn’t rise or set, nor do we

see it rise or set, because, if the earth rotates on his axis,

what do we mean by rising and setting ..."

- Giordano Bruno,

from the Vatican summary of

Bruno's trial ([5]).

"I fought, and that's a lot. I thought I could win ... but

nature and luck curbed my endeavour. But it's already something

that I took up the struggle, because I see that victory is in

the hands of Fate. In me was what was possible and what no

future century will be able to deny to me: what a winner could

give from his own; that I did not fear death, that I did not

submit, my face firm, to anyone of my breed; that I preferred

courageous death to pavid life."

- Giordano Bruno,

De Monade

"I cleave the heavens, and soar to the infinite. What others see

from afar, I leave far behind me."

- Giordano Bruno

Notes

-

The Pope & the Heretic, Michael

White

-

Vatican Secret Archives: Summary of

the trial against Giordano Bruno, Rome, 1597

-

Luigi Firpo, Il processo di Giordano

Bruno, 1993

-

Site of Bruno's execution:

41°53′44″N, 12°28′20″E.

-

Alan Powers, Bristol Community

College, Campania Felix: Giordano Bruno’s Candelaio and Naples

accessed 27 May 2007

-

Hans-Volkmar Findeisen: „Gegenpapst

und Designer des Darwinismus“ – Wer kennt heute eigentlich noch

Ernst Haeckel? (in German) accessed 27 May 2007

-

Sheila Rabin at the Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Thus, in 1600 there was no official

Catholic position on the Copernican system, and it was certainly

not a heresy. When Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) was burned at the

stake as a heretic, it had nothing to do with his writings in

support of Copernican cosmology." Nicolaus Copernicus in the

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (online, accessed 19

November 2005).

-

Similarly, the Catholic Encyclopedia

(1908) asserts, "Bruno was not condemned for his defense of the

Copernican system of astronomy, nor for his doctrine of the

plurality of inhabited worlds, but for his theological errors,

among which were the following: that Christ was not God but

merely an unusually skilful magician, that the Holy Ghost is the

soul of the world, that the Devil will be saved, etc." Turner,

William. "Giordano Bruno.” 1908. Catholic Encyclopedia accessed

2 Jan. 2007.

-

Vatican Secret Archives accessed 3

November 2006.

-

[1] Max Tegmark, Parallel Universes,

2003

References

-

Bruno, GiordanoThe Acentric

Labyrinth. Giordano Bruno's Prelude to Contemporary Cosmology,

Ramon G. Mendoza PhD, 1995, ISBN 1-85230-640-8

-

Cause, Principle and Unity : And

Essays on Magic by Giordano Bruno, ISBN 0-521-59658-0

-

The Cabala of Pegasus by Giordano

Bruno, ISBN 0-300-09217-2

-

"Writings of Giordano Bruno"

-

The Pope & the Heretic, Michael

White, 2002, ISBN 0-06-018626-7.

-

Giordano Bruno, J. Lewis McIntyre.

-

Giordano Bruno and Renaissance

Science, Hilary Gatti, 2002, ISBN 0-8014-8785-4

-

Giordano Bruno: His Life and

Thought, With Annotated Translation of His Work -On the Infinite

Universe and Worlds,Dorethea Singer,1950.

-

Giordano Bruno: The Forgotten

Philosopher, John Kessler.

-

Giordano Bruno, Paul Oskar

Kristeller, Collier's Encyclopedia, Vol 4, 1987 ed., pg. 634

-

Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic

Tradition, Frances Yates, ISBN 0-226-95007-7

-

Eros and Magic in the Renaissance,

Ioan P. Couliano, ISBN 0-226-12315-4.

-

Il processo di Giordano Bruno, Luigi

Firpo, 1993

-

Giordano Bruno,Il primo libro della

Clavis Magna, ovvero, Il trattato sull'intelligenza artificiale,

a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore.

-

Giordano Bruno,Il secondo libro

della Clavis Magna, ovvero, Il Sigillo dei Sigilli, a cura di

Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore.

-

Giordano Bruno, Il terzo libro della

Clavis Magna, ovvero, La logica per immagini, a cura di Claudio

D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

-

Giordano Bruno, Il quarto libro

della Clavis Magna, ovvero, L'arte di inventare con Trenta

Statue, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

-

Giordano Bruno L'incantesimo di

Circe, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

-

Giordano Bruno, De Umbris Idearum, a

cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

-

Guido Del Giudice, La coincidenza

degli opposti, Di Renzo Editore, ISBN 8883231104 , 2005

-

Giordano Bruno, Due Orazioni: Oratio

Valedictoria - Oratio Consolatoria, a cura di Guido del Giudice,

Di Renzo Editore, 2007

Legacy

-

The 20-km diameter crater Giordano

Bruno, named in Bruno's honor, is located on the moon at

103°east lunar longitude, 36° north lunar latitude. It is

believed to have been created by a meteorite impact in 1178,

witnessed by five English monks as related in Carl Sagan's

Cosmos.

-

In 1926 the Theosophical

Broadcasting Station Pty Ltd, owned by interests associated with

the local branch of Theosophical Society Adyar, was granted a

radio broadcasting license in Sydney, Australia. The station's

call sign, "2GB" was chosen to honour the Italian philosopher

who was much admired by Theosophists. Although the ownership of

the station subsequently passed to strictly commercial interests

the call sign is retained.

|